Editor’s note: This article was originally published Aug. 13, 2025, and has been updated to include new text and illustrations featured in the January 2026 issue of Astronomy.

Using an artificial intelligence algorithm, astronomers have discovered a new type of supernova that likely results from the merging of a dying star and its black hole companion.

In July 2023, the Zwicky Transient Facility detected supernova SN 2023zkd, located 730 million light-years from Earth. Six months later, in January 2024, an AI algorithm known as the Lightcurve Anomaly Identification and Similarity Search (LAISS) flagged the explosion as anomalous.

The detection and subsequent analysis were conducted by a team led by the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) and MIT as part of the Young Supernova Experiment (YSE). The alert from LAISS triggered immediate and widespread follow-up observations, which proved essential in unraveling the supernova’s highly unusual nature.

Those observations revealed two behaviors that depart from a typical supernova. First, the star had been brightening for at least four years before its final detonation. Second, the explosion didn’t fade away as expected, but dramatically rebrightened about 240 days later. Both can be explained, the team says, if the star’s death was triggered by merging with a black hole companion.

The team’s findings were published Aug. 13 in The Astrophysical Journal. “We think this might be part of a whole class of hidden explosions that AI will help us discover,” said V. Ashley Villar, an astronomer at Harvard University and a co-author on the study, in a CfA press release.

A cosmic anomaly

A star spends its life in a delicate balancing act, with the outward pressure from nuclear fusion in its core pushing against the inward crush of gravity. As a star runs out of hydrogen — its main fuel for fusion — it begins fusing heavier and heavier elements, until the chain reaches iron. Fusing iron consumes energy rather than releasing it, so the star’s engine abruptly shuts off. This shatters the star’s equilibrium: With nothing to halt its collapse, gravity wins. If the star is massive enough, the core implodes and the star’s outer layers rebound off the newly formed, ultradense object, launching a huge shock wave. This is known as a standard type II supernova.

RELATED: The different types of supernovae explained

SN 2023zkd belongs to a special subclass called type IIn. The n signifies the explosion happens inside a dense cloud of gas the star previously shed. The supernova’s shock wave slamming into this material creates a complex light show.

But even for this chaotic class of events, SN 2023zkd stood out as strange: By analyzing archival data, the team found that before it exploded, it had been brightening for four years. The team calls this activity the “precursor” period, and splits it into two phases: Precursor A, a long initial period of steady brightening; and Precursor B, a final, accelerated ramp-up.

Uncovering this highly unusual behavior was an “ ‘aha’ moment,” says the study’s lead author Alex Gagliano, an astronomer and postdoctoral research fellow with the NSF-funded Institute for AI and Fundamental Interactions (IAIFI). The “years-long ramp-up to the explosion … is a very clear prediction of a scenario involving a star and a black hole.”

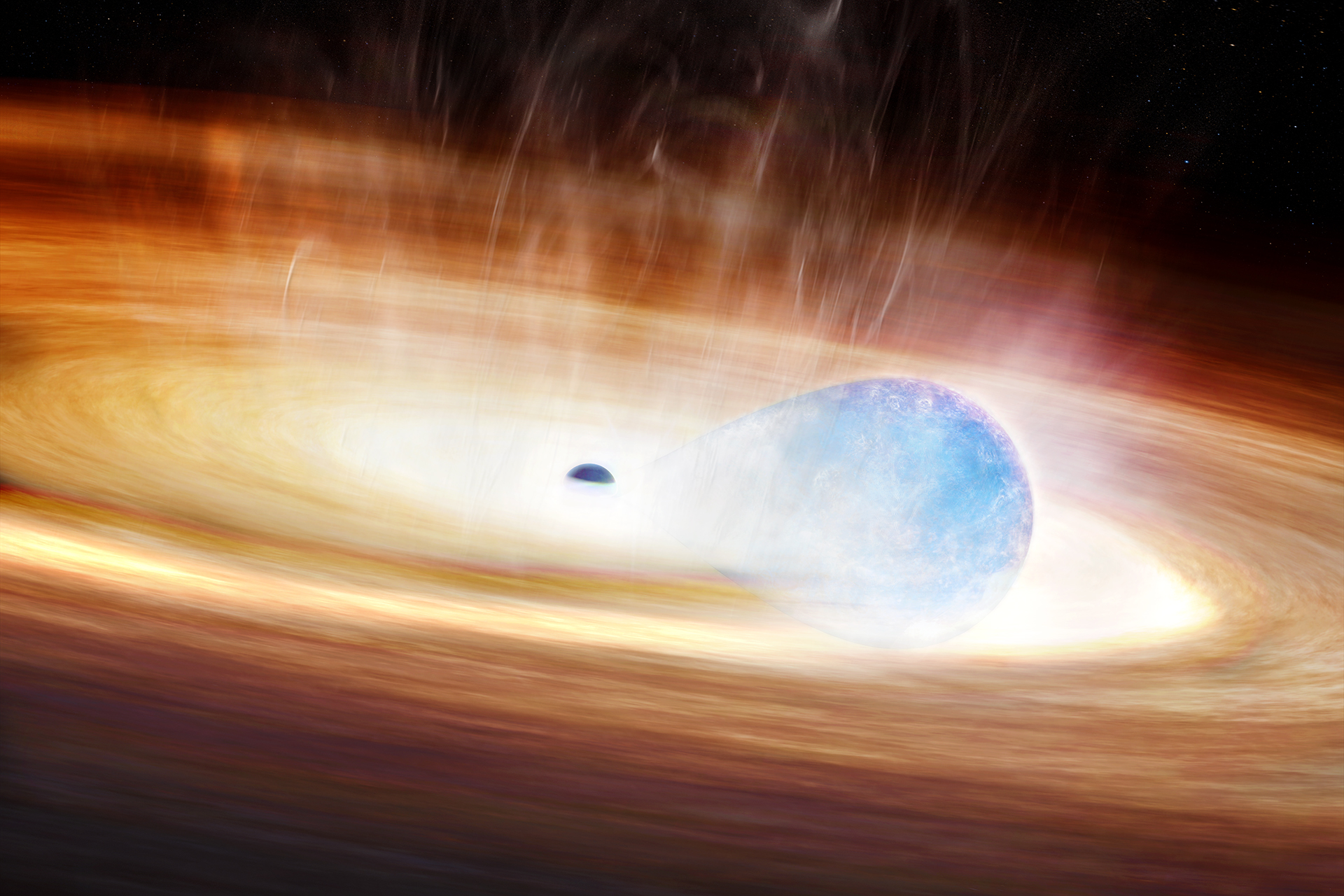

The team concluded that the two objects were in a “really, really tight binary,” spiraling in toward each other. This process was “very messy,” Gagliano says, and formed a complex system with multiple structures.

First, as the black hole yanked material off the star, some of that material swirled toward the black hole, forming an accretion disk wrapped around it. As this material heated up prior to disappearing into the black hole, it generated the Precursor A emission. At the same time, some of the material shed from the star formed a larger disk outside both the black hole and the star, creating a dense so-called circumbinary disk enveloping the entire system.

Meanwhile, the furious interplay between the star and black hole also ejected material along the system’s poles, forming clouds of gas above and below its orbital plane. The origin of this polar material — whether it is from the star directly or from the circumbinary disk — is still an open question.

A helpful, if imperfect, analogy for the system’s resulting structure is the Homunculus Nebula surrounding the star Eta (η) Carinae, which also features a pinched equatorial disk and large polar lobes of ejected gas.

Then, as the star and black hole chaotically spiraled toward each other more tightly in the year before the explosion, their interaction created Precursor B, the final, bright ramp-up emission.

A double-peaked explosion

The star’s unusual preexplosion activity was only half of the mystery. After a supernova detonates, its brightness typically climbs to a single, brilliant peak before beginning a steady fade. And SN 2023zkd followed this script at first.

But after several months of fading as expected, it rebrightened, reaching a second, nearly as brilliant peak about 240 days after the first. This extremely rare occurrence was the second major clue that this event was unlike a standard stellar explosion.

Using computer models, the team ound that the first peak came from the shock wave hitting the diffuse polar clouds, and the second, more sustained peak was caused by it slamming into the dense circumbinary disk.

The sequence is counterintuitive: Why would the collision with the circumbinary disk — which lies inside the polar clouds — create the second peak? The answer is an observational effect driven by the structures’ differing densities, says Gagliano. When the supernova’s blast wave moved through the system, the low-density polar clouds were swept up rapidly. As the shock wave moved through these clouds and excited their atoms, it created a huge, expanding photosphere — the visible surface layer from which light can escape — inside of which “everything is so hot that it’s opaque,” Gagliano says.

The shock wave also slammed into the denser circumbinary disk, but its material was being swept up more slowly. “The thinking is that the photosphere … very quickly overtakes the [circumbinary] disk,” so that the disk is effectively concealed inside the photosphere even though it is producing light, Gagliano says.

Only as the outer material cooled and the photosphere began to recede did the disk become visible, powering the dramatic rebrightening. “There’s a transition where your outermost photosphere is not that low-density material. It’s the interaction that’s happening between the disk and the explosion. And so your photosphere moves inward and inward and inward until eventually you’re just seeing the interaction with the disk, that powers then that second peak,” Gagliano says.

A new window on stellar death

The violent inspiral and complex gas structures pointed to one culprit: a black hole companion, which triggered the star’s explosive death. In this scenario, stresses induced by the black hole’s gravity as the two circled increased the pressure in the star’s core until it could no longer support itself, inducing a core-collapse supernova. It’s an event that has been theorized but never observed, and it addresses a long-standing question in astronomy.

“For decades, there’s been these debates about whether material coming off of a star in the millennia to years before it explodes is caused by internal changes … or is it internal changes driven by dynamical interactions with a companion?” Gagliano says. This discovery, he adds, provides confirmation that companions can indeed play a “determining role in the explosion itself.”

While the merger-induced supernova is the leading theory, the team also considered an alternative scenario called tidal disruption, Gagliano says, in which the black hole tears the star apart before it can explode. In that case, the brilliant flash of light that looked like a supernova was not a traditional supernova, but instead the two objects spiraled together until the star was completely consumed. If this were the case, however, the team would expect “earlier, brighter emission that we didn’t see in this event,” Gagliano says.

Fittingly, a story that began with an automated algorithm points to a future where astronomy and artificial intelligence work hand in hand. As next-generation observatories like the Vera C. Rubin Observatory begin to generate an unprecedented flood of data, intelligent systems like LAISS will be indispensable.

RELATED: Here are the first-ever images released by the Vera C. Rubin Observatory

In the case of SN 2023zkd, the warning from the LAISS algorithm turned the team’s attention to the event long before the rebrightening. “To our eyes, the supernova was not too unusual, but our algorithm was luckily able to pick up on it as something unusual.”

With this discovery, astronomers have a blueprint for an entirely new class of stellar death. The goal now is to find more. If, with the help of AI, astronomers can build a sample of these events and capture detailed spectra, Gagliano explains, “then you can start to make population-level statements that we just have never been able to make before.” SN 2023zkd has opened a new window onto the complex lives of massive stars.

“We’re now entering an era where we can automatically catch these rare events as they happen, not just after the fact,” Gagliano said in a press release. “That’s incredibly exciting.