Friday, September 9

Mercury reaches its stationary point in Virgo today at 4 P.M. EDT. It will now begin moving westward, or retrograde, while also reducing its elongation from the Sun. The solar system’s smallest planet will reach inferior conjunction later this month.

With a nearly Full Moon in the sky, we’re limited to bright objects tonight (and much of this week). Just in time for fall, let’s find the Wild Duck Cluster, formally cataloged as M11. This young open cluster located in the small constellation Scutum, which sits adjacent to the mighty eagle Aquila. The easiest way to find M11 is to look about 3° west-southwest of the two stars that form Aquila’s tail: Lambda (λ) and 12 Aquilae. M11 is visible to keen-eyed observers with no optical aid on dark nights, though tonight, the bright moonlight will wash it out unless you look with binoculars or a telescope. In total, the cluster spans about 14′ and glows at magnitude 5.8. It contains nearly 3,000 stars about 220 million years old.

Nearby is the Scutum Star Cloud, a rich, star-filled region that you can also enjoy in the same wide field of view. Admittedly, this star-studded sight will be much better on a moonless night, so we’ll return when our bright satellite has moved on.

Sunrise: 6:35 A.M.

Sunset: 7:19 P.M.

Moonrise: 7:24 P.M.

Moonset: 5:23 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (99%)

*Times for sunrise, sunset, moonrise, and moonset are given in local time from 40° N 90° W. The Moon’s illumination is given at 12 P.M. local time from the same location.

Saturday, September 10

Full Moon occurs at 5:59 A.M. EDT. This Full Moon is also called the Harvest Moon because it falls closest to the autumnal equinox, which occurs later in the month. But September’s Full Moon isn’t always called the Harvest Moon — when October’s Full Moon falls closer to the equinox, it is referred to as the Harvest Moon. If that happens, September’s Full Moon is instead called the Corn Moon.

You can catch the bright Moon rising just after sunset, located just on the border between Aquarius and Pisces. The Moon passed 3° south of Neptune at 3 P.M. EDT; if you’re looking for a challenge, pull out your telescope to see if you can spot the planet’s dim blue disk, now nearly 5° north-northwest of our satellite. At magnitude 7.7, Neptune is typically readily visible in binoculars, but the Moon’s bright light will likely mean you’ll need a bit more aperture to pull the ice giant out from the background. The Moon will proceed into Pisces as the hours go by, passing close to Jupiter tomorrow.

Sunrise: 6:36 A.M.

Sunset: 7:17 P.M.

Moonrise: 7:50 P.M.

Moonset: 6:38 A.M.

Moon Phase: Full

Sunday, September 11

The Moon passes 1.8° south of Jupiter at 11 A.M. EDT. By this evening, our satellite has moved into Cetus and sits 6.5° east of the gas giant two hours after sunset.

While the bright Moon is rising in the east, let’s turn our gaze to the west. There, you’ll find magnitude 0 Vega, which ranks as the fifth-brightest star in the sky. Less than 2° to Vega’s northeast is Epsilon (ϵ) Lyrae, also known as the Double Double star. That’s because, when viewed through a telescope with a magnification of 75x or greater, this single point of light splits into two distinct pairs of stars. The northern pair is cataloged as Epsilon1, while the southern duo is Epsilon2. Epsilon1 is composed of two stars with magnitudes 5.1 and 6, separated by 2.6″; Epsilon2 contains stars with magnitudes 5.1 and 5.4, separated by 2.3″. See if you can capture both pairs together with bright Vega in a single field of view.

Sunrise: 6:37 A.M.

Sunset: 7:15 P.M.

Moonrise: 8:15 P.M.

Moonset: 7:50 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waning gibbous (98%)

Monday, September 12

Orion and his two loyal hunting dogs stand high in the early-morning sky. An hour before sunrise, look east to find the familiar three-star asterism of Orion’s Belt, as well as his trusty sword hanging some 3.7° south of the easternmost star in the belt, magnitude 1.7 Alnitak. The sword, which appears fuzzy to most people’s eyes, contains the famous Orion Nebula (M42), a rich, nearby star-forming region that’s absolutely stunning through a telescope. Even with the waning gibbous Moon in the sky, it’s worth taking a look if you’ve got a medium or even small scope.

Some 30° east of Orion’s Belt is Canis Minor, Orion’s smaller hunting dog. The brightest star in this constellation is magnitude 0.4 Procyon, which marks the Little Dog’s nose. Just 11.4 light-years away, Procyon is the sky’s eighth-brightest star.

Let’s slide up to the top of that chart and next visit Sirius, the brightest star in the sky. Also called the Dog Star, this luminary marks the nose of Canis Major the Big Dog and sits nearly 26° southwest of Procyon. With a Greek name that literally means “searing” or “scorching,” you can’t miss this magnitude –1.4 star! But there’s something else you might not miss: This close to the horizon, Sirius may appear to violently twinkle or dance in place. Turn binoculars or a telescope on it, and you may even see it appear to change color, flickering like you’re looking at it through a kaleidoscope. This effect, called scintillation, occurs when you observe starlight through Earth’s turbulent atmosphere, which muddies the view. The brighter a star and the closer to the horizon it sits, the larger the effect.

Sunrise: 6:38 A.M.

Sunset: 7:14 P.M.

Moonrise: 8:39 P.M.

Moonset: 8:59 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waning gibbous (93%)

Tuesday, September 13

While the Double Double we observed in Lyra earlier this week required a telescope to fully split, tonight we’re going to test your naked-eye skills. First, find the Big Dipper, that famous asterism in Ursa Major up north. Early in the evening, it’s right-side up and swinging down below Polaris, the North Star. Locate the last star at the tip of the Big Dipper’s handle — that’s Alkaid, also known as Eta (η) Ursae Majoris.

Now, look one star in, at the “kink” in the handle. Do you see one star, or two? The bright, obvious star most people recognize in the handle is magnitude 2.3 Mizar. But just under 12′ to its northeast is magnitude 4 Alcor — much fainter, but still within naked-eye visibility. Some people like to use this widely separated pair as a test of visual acuity. How do you score?

Mizar and Alcor may look close in the sky, but they’re not considered a binary pair. That’s because they are separated by a full light-year, so can’t be bound together and orbiting each other. Nonetheless, they do seem related, as both are traveling together through the galaxy in the same direction and with the same speed, along with several other stars in the Big Dipper that together form the Ursa Major Moving Group.

Sunrise: 6:39 A.M.

Sunset: 7:12 P.M.

Moonrise: 9:05 P.M.

Moonset: 10:07 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waning gibbous (87%)

Wednesday, September 14

The Moon passes 0.8° north of Uranus at 7 P.M. EDT. If you’d like to try to spot the pair, you’ll need to wait until they rise after dark, located in Aries the Ram. The Moon is now just less than 3.5° east of the ice giant, whose magnitude 5.7 glow may be a bit difficult to pick out in binoculars or a telescope with our satellite so close. Don’t let that stop you from trying, however, to spot Uranus’ 4″-wide grayish disk west of the Moon.

According to NASA, today also begins the shortest solar day of the year. While days on Earth are always considered to be 24 hours long, the length of the solar day — defined as the time between two successive instances of when the Sun is highest in the sky — varies throughout the year. The shortest day, as measured between two subsequent solar noons, generally occurs in September, and this year begins at solar noon today and ends at solar noon tomorrow. Its length is 23 hours, 59 minutes, and 38.6 seconds.

Sunrise: 6:40 A.M.

Sunset: 7:10 P.M.

Moonrise: 9:33 P.M.

Moonset: 11:14 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waning gibbous (80%)

Thursday, September 15

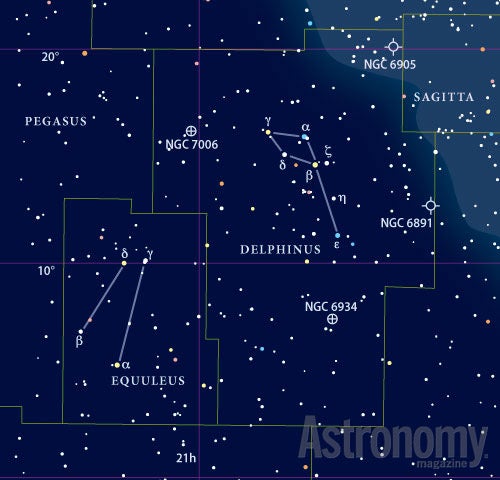

Look about 50° above the eastern horizon shortly after sunset tonight and you’ll discover the small, kite-shaped constellation Delphinus the Dolphin. This star pattern sits some 15° east-northeast of the bright star Altair in Aquila.

Delphinus ranks 69th in size among the constellations in terms of area and is bordered by Equuleus, Pegasus, Vulpecula, Sagitta, Aquila, and Aquarius. Its brightest star, magnitude 3.6 Rotanev, is actually cataloged as its beta star; Alpha (α) Delphini, also known as Sualocin, is magnitude 3.8. Together with Gamma (γ) and Delta (δ) Delphini, these stars form a diamond-shaped “lozenge” asterism called Job’s Coffin, which fits neatly into the field of view of many binoculars. Several of these stars are binaries, with Gamma perhaps the most striking through a telescope. Separated by 10″, its components are slightly different colors, one yellow and one orange.

Sunrise: 6:41 A.M.

Sunset: 7:09 P.M.

Moonrise: 10:04 P.M.

Moonset: 12:19 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waning gibbous (71%)

Friday, September 16

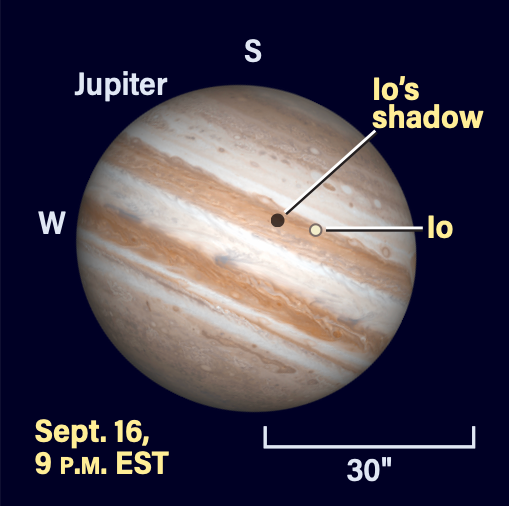

The mighty planet Jupiter is nearing opposition, drumming up some neat effects. One is that transits of its Galilean moons and their shadows happen at nearly the same time. Observing two such events only a few days apart will reveal marked differences and tonight you can get started, as Io is already transiting Jupiter’s great disk when the planet clears the horizon in the Midwest.

Jupiter, shining at magnitude –2.9 all month, is located in Pisces the Fish; you’ll find it rising in the east around 7:30 P.M. local time, slowly climbing out of the haze near the horizon over the next few hours. As it rises, the gas giant sits about 12° to the lower left of the Circlet asterism.

By around 9 P.M. EDT, both Io and its shadow are nearing the center of the disk, with Io slightly trailing the dark blot. They slip off the disk just 15 minutes apart, starting with the shadow’s disappearance around 10:13 P.M. EDT. Mark your calendar for exactly one week from today: On the 23rd, Io will transit again, this time nearly overlapping with its shadow as the two travel together across Jupiter’s disk.

The ice giant Neptune reaches opposition today at 6 P.M. EDT — we’ll focus on this event in next week’s column, so stay tuned! The Moon also passes 4° north of Mars at 10 P.M. EDT, though neither are visible at that time. We’ll check them out next Saturday in the early-morning sky.

Sunrise: 6:42 A.M.

Sunset: 7:07 P.M.

Moonrise: 10:40 P.M.

Moonset: 1:23 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waning gibbous (62%)