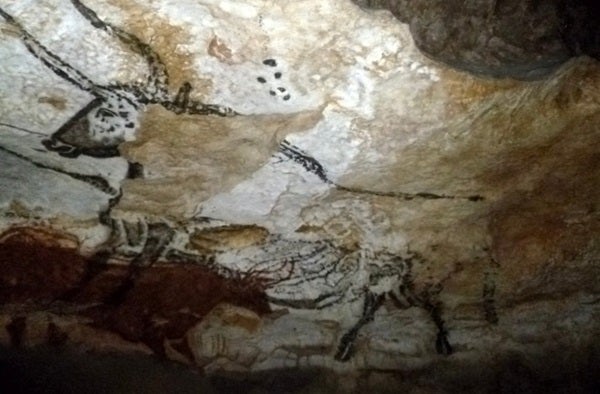

In the Lascaux caves of southwestern France, which are famously adorned with 17,000-year-old paintings, the artist’s subject is almost always a large animal.

But hovering above the image of one bull is an unexpected addition: a cluster of small black dots that some scholars interpret as stars. Perhaps it is the eye-catching Pleiades, which Paleolithic hunter-gatherers would have seen vividly in the unpolluted sky.

Claims of prehistoric astronomy are controversial. Even if true, we frequently trace our cosmic perspective instead to Nicolaus Copernicus, who in 1543 set a steady course by proving that Earth revolves around the Sun; to Galileo Galilei and Johannes Kepler, who refined the heliocentric theory a generation later; and to all their successors, who in just a few centuries (with the considerable advantage of telescopes and other advanced technology) have produced an astonishingly detailed map of the universe.

Yet for tens of thousands of years, humans studied the heavens with just the naked eye and, eventually, crude instruments. They got plenty wrong but the stargazers of old weren’t slouches, and by a few thousand years ago they’d become surprisingly sophisticated.

“It is no exaggeration to say that astronomy has existed as an exact science for more than five millennia,” writes the late science historian John North.

Reading the sky

Traces of those early observers, of the way they interpreted the cosmos, have reached us in the form of tantalizing artifacts. For example, dating to roughly 1600 B.C., we have what is perhaps the first portrait of the universe: the Nebra Sky Disk.

Unearthed just two decades ago in what is now eastern Germany, this 12-inch bronze circle is inlaid with gold strips in the shape of the Sun (or Full Moon), a crescent Moon, and various stars. It may have been used for religious or agricultural purposes, but its significance to those who made it is unclear.

Deeper meanings aside, experts generally agree the disk is the oldest known concrete depiction of astronomical phenomena, and that it’s more than a vague abstraction. One dense clump of stars seems to represent the Pleiades (and more accurately than the Lascaux cave painting).

If the Seven Sisters keep popping up in different times and places, it might not be coincidence — the cluster has drawn attention throughout recorded history, just by standing out from its solitary neighbors. Some cultures used it as a signal for when to plant and harvest crops.

Searching for meaning

Around the same time, the ancient Egyptians, who already had a long history of astronomical observation, were developing star charts. These schematic illustrations described the movements of various stars — possibly to keep priests punctual for their nighttime rituals, or perhaps to guide the dead in the afterlife, since the illustrations often appeared inside coffins.

Later, likely in the first century B.C., the Egyptians got more imaginative with the Dendera Zodiac. At first, this bas-relief, which decorated the ceiling of a temple dedicated to the god Osiris, looks like a random menagerie: rams, lions, crocodiles and more, arranged in a circle.

But soon after its discovery in 1799, Egyptologists recognized it as a tableau of the night sky, organized around many of the same constellations we still use today.

The Babylonians of the first millennium B.C. recorded their astronomical knowledge in a similar way, by inscribing on clay tablets the heliacal rising of important stars — that is, the day that a star first appears above the horizon each year. From these lists, they produced “planispheres,” instruments that showed which stars (and, importantly for their astrological predictions, which constellations) would be visible at any given time.

Incorporating Greek philosophy

The word “cosmos” comes from ancient Greece, where it signified not simply the universe, but the universe as a harmonious, well-ordered whole. Though these classical philosophers took what they found useful from the Egyptian and Babylonian traditions, they broke with the supernatural elements of astrology, opting for a celestial mechanics based on (more or less rigorous) reasoning and mathematics.

One method of cosmic display at this time was the armillary sphere, a globe-like model with several rings to illustrate the motion of the Sun, Moon, and stars. Earth, by Greco-Roman reckoning, stood still at the center.

In this case, the sphere is “Ptolemaic,” named for the Alexandrian astronomer Ptolemy, whose geocentric paradigm dominated Western belief until the 1500s. Spheres that instead show Earth orbiting the Sun are, naturally, called “Copernican.”

For his lofty picture of the heavens, the Greek philosopher Aristotle took geocentrism to its logical conclusion. As he saw it, the universe consisted of a series of concentric shells revolving around our planet — one each for the Sun, the Moon, every other planet, the fixed stars, and an outermost level for the “prime mover,” a being which he deduced must have been necessary to set everything in motion.

Moving toward modernity

This God-like vision meshed well with the rise of Christianity. Throughout the Medieval period, it became conventional wisdom — despite the theoretical acrobatics required to square it with actual astronomical observations (in particular, retrograde planetary motion).

Aristotle and Ptolemy’s combined vision held such sway, in fact, that by the 14th century, Italian poet Dante Alighieri structured the world of his Divine Comedy around it. And all he had to do was add a second set of concentric hells.

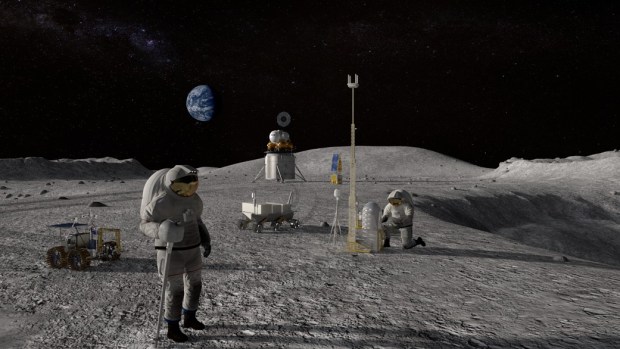

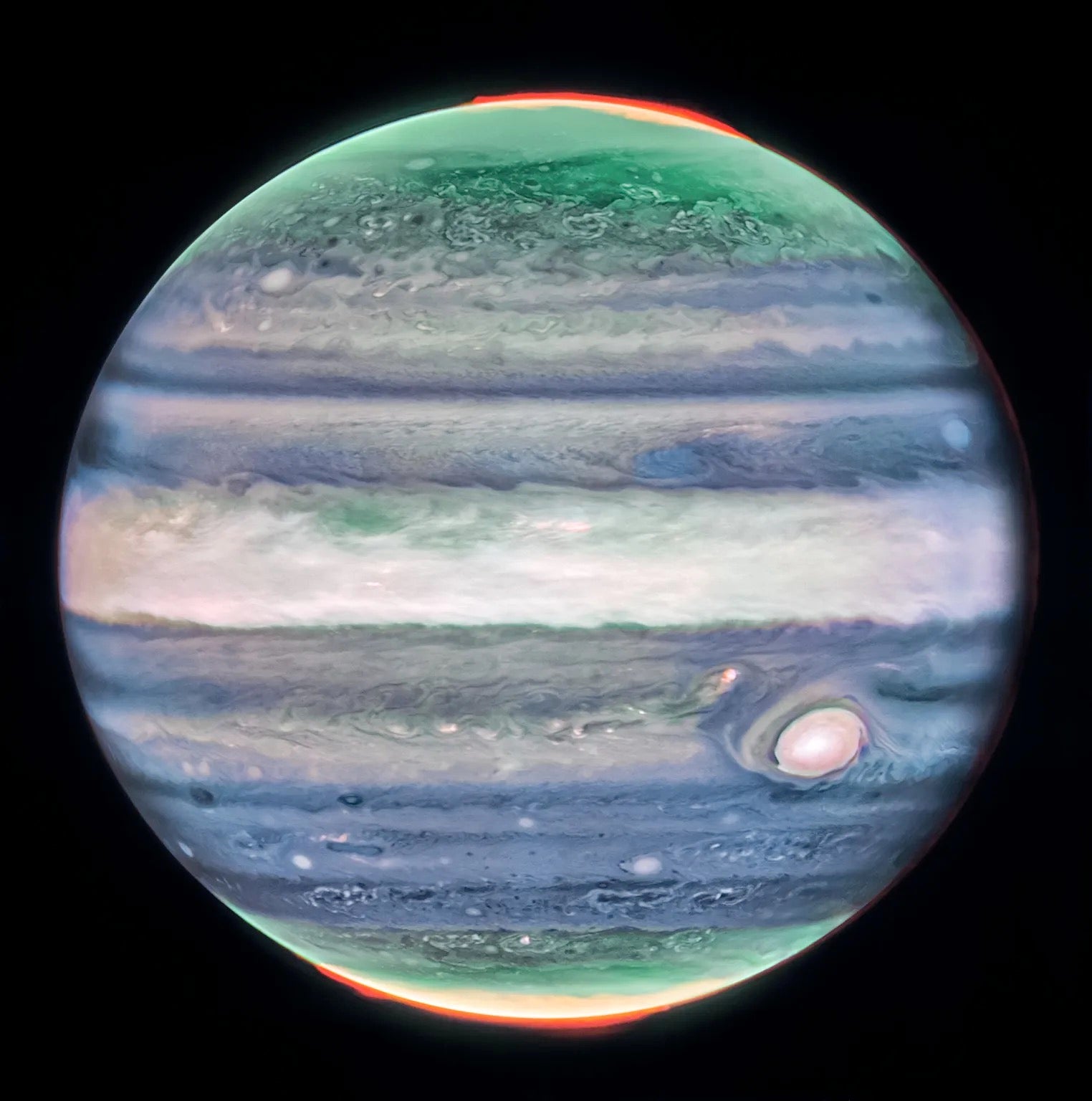

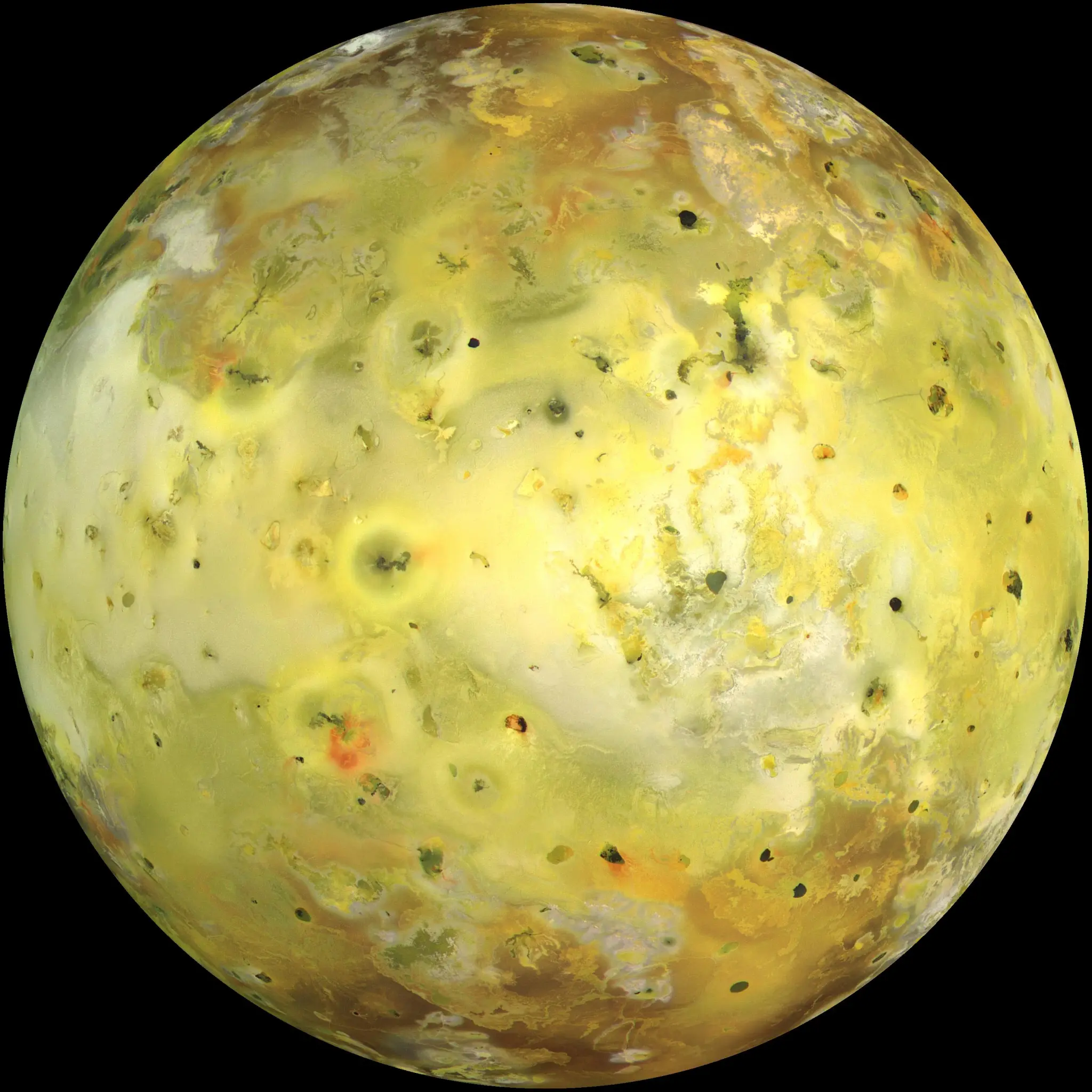

The Copernican revolution and its aftermath have long since swept away these antiquated notions, of course. But with every scientific advance, every mind-blowing, deep-space image from the James Webb Space Telescope, we expand our view of the cosmos and continue the process that those cave-dwellers began when they stepped outside to gaze up at the sky.