For the first time, astronomers have discovered evidence for a giant planet orbiting a tiny, dead white dwarf star. And, surprisingly, the Neptune-sized planet is more than four times the diameter of the Earth-sized star it orbits.

“This star has a planet that we can’t see directly,” study author Boris Gänsicke from the University of Warwick said in a press release. “But because the star is so hot, it is evaporating the planet, and we detect the atmosphere it is losing.” In fact, the searing star is sending a stream of vaporized material away from the planet at a rate of some 260 million tons per day.

The new discovery serves as the first evidence of a gargantuan planet surviving a star’s transition to a white dwarf. It suggests that evaporating planets around dead stars may be somewhat common throughout the universe. And because our Sun, like most stars, will also eventually evolve into a white dwarf, the find could even shed light on the fate of our solar system.

An unexpected pairing

The white dwarf in question, dubbed WDJ0914+1914, sits about 1,500 light-years away in the constellation Cancer. Although the white dwarf is no longer undergoing nuclear fusion like a normal star, its lingering heat means it’s still a blistering 49,500 degrees Fahrenheit (25,000 Celsius). That’s some five times hotter than the Sun.

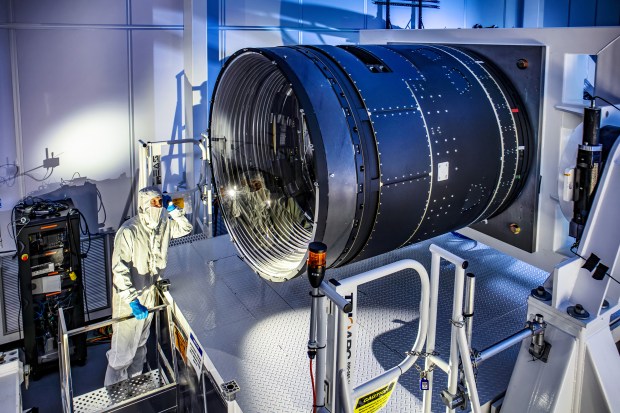

Researchers initially flagged the smoldering stellar core for follow-up after sifting through about 7,000 white dwarfs identified by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. When the team analyzed the unique spectra of WDJ0914+1914, they detected the chemical fingerprints of hydrogen, which is somewhat unusual. But they also picked out signs of oxygen and sulfur — elements they had never seen in a white dwarf before.

“It was one of those chance discoveries,” Gänsicke said in a European Southern Observatory (ESO) press release. “We knew that there had to be something exceptional going on in this system, and [we] speculated that it may be related to some type of planetary remnant.”

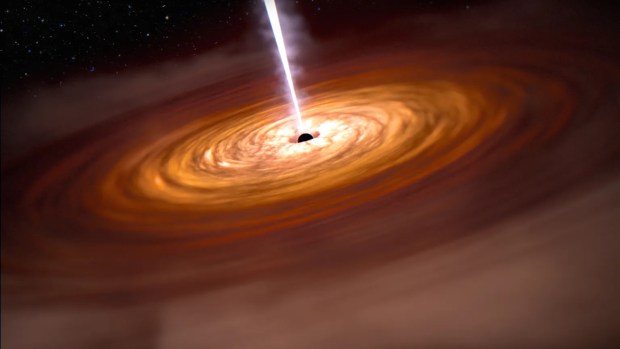

So, in order to get a better grasp of what was happening in the strange system, the team used the X-shooter instrument on the ESO’s Very Large Telescope in Chile to carry out follow-up observations. Based on the more detailed look, the researchers learned that the unusual elements they thought were embedded in the white dwarf were actually coming from a disk of gas churning around the dead star.

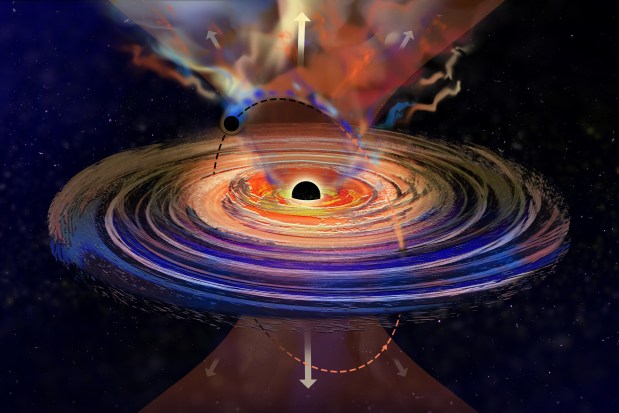

“At first, we thought that this was a binary star with an accretion disk formed from mass flowing between the two stars,” said Gänsicke. “However, our observations show that it is a single white dwarf with a disk around it roughly 10 times the size of our Sun, made solely of hydrogen, oxygen, and sulfur. Such a system has never been seen before, and it was immediately clear to me that this was a unique star.”

After realizing just how unusual the white dwarf really was, the team shifted their focus to figuring out what the heck could create such a system.

“It took a few weeks of very hard thinking to figure out that the only way to make such a disk is the evaporation of a giant planet,” said Matthias Schreiber, an astronomer at the University of Valparaiso in Chile, who was vital to determining the past and future evolution of the bizarre system. Their detailed analysis of the disk’s composition matched what astronomers would expect if the guts of an ice giant like Uranus and Neptune were vaporized into space.

Based on Schreiber’s calculations, the white dwarf’s extreme temperature means it’s bombarding the nearby giant planet — which is located 0.07 astronomical unit (AU) from the star, where 1 AU is the Earth-Sun distance — with high-energy photons. This is causing the planet to lose its mass at a rate of more than 3,000 tons per second.

But according to the paper, published Wednesday in Nature, “As the white dwarf continues to cool, the mass loss rate will gradually decrease, and become undetectable in [about 350 million years.] And by then, the paper adds, the giant planet only will have lost “an insignificant fraction of its total mass,” or about 0.04 Neptune masses.

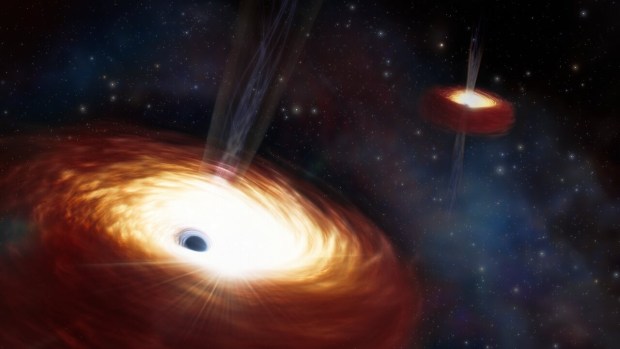

Because the giant planet is located so close to the white dwarf, the researchers say it should have been destroyed during the stars’ red giant phase. That is, unless it migrated inward after the star transitioned to a white dwarf.

“This discovery is major progress because over the past two decades we had growing evidence that planetary systems survive into the white dwarf stage,” said Gänsicke. “We’ve seen a lot of asteroids, comets, and other small planetary objects hitting white dwarfs, and explaining these events requires larger, planet-mass bodies farther out. Having evidence for an actual planet that itself was scattered in is an important step.”

The ultimate fate of our solar system

In 5 billion years, when the Sun burns through the last of the hydrogen in its core, it will move on to fusing concentric shells of hydrogen around its now-inert core. This unstable process will cause the Sun to balloon into a red giant, meaning it will swallow Mercury, Venus, and likely Earth.

But as the Sun expands, its gravitational grasp on its outer envelope of material gets more and more tenuous. Eventually, it will shed its outer layers into space. And once it does that, an alien astronomer would see a beautiful planetary nebula surrounding the Sun’s burnt-out, incredibly hot core — known as a white dwarf.

In a companion paper also published Wednesday in Astrophysical Journal Letters, Schreiber and Gänsicke explore this scenario, detailing how the future white-dwarf Sun should, like WDJ0914+1914, evaporate our solar system’s giant planets.

“In a sense,” said Schreiber, “WDJ0914+1914 is providing us with a glimpse into the very distant future of our own solar system.”

[Editor’s Note: This story has been corrected from an earlier version. The planet orbits 0.07 astronomical units from the star.]