The researchers, led by the SETI Institute’s Cristina Dalle Ore, published their findings Wednesday, May 29, in the journal Science Advances.

A detective story

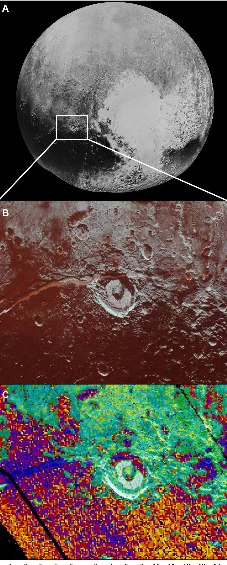

To reach their conclusion of an underground liquid ocean on Pluto, Dalle Ore’s team first had to piece together a likely story explaining it. Pluto’s color was their first clue. When New Horizons began returning images of Pluto, the red stains covering large regions of the world jumped out at researchers. They were a clear sign that Pluto’s icy surface is not all water ice, but contains other elements. Virgil Fossae was one of the particularly red features in Pluto’s so-called Cthulhu region, the dark area to the left of Pluto’s bright and famous heart. So the researchers looked at spectral information for that region, to learn what kinds of materials are present.

They found a strong sign of ammonia. But ammonia is easily broken up by the sun’s ultraviolet light and charged particles, and by cosmic rays. So according to calculations, the researchers think the surface ammonia must have been deposited within the last billion years. That may sound like a long time to humans, who only came into existence a few hundred thousand years ago. But it’s not terribly long in a geologic sense.

Perhaps more importantly, the ammonia is located in a region that looks quite young, since the pattern of ice around it still looks like it erupted from an ice volcano and hasn’t been destroyed by meteors or covered over since.

And while neither clue is conclusive on its own, together they make a much stronger argument. Ammonia mixed into water lowers its freezing point. Planetary researchers have long posited that a liquid ocean with a healthy dollop of ammonia – something like a third of the mixture – would stay liquid even though Pluto’s surface, far from the sun, is frigid and well below normal freezing temperatures.

Pluto’s rugged appearance since New Horizon’s first images have hinted that cryovolcanism is either a recent or ongoing activity on the dwarf planet. And active ice volcanoes require something under Pluto’s surface to be liquid or at least slushy, capable of squeezing and flowing through cracks to the surface.

The ammonia leaked to the surface might provide an explanation for how icy Pluto has kept liquid reservoirs underground, perhaps even to this day.

Are you ready to learn more about what New Horizons learned at Pluto? Check out our free downloadable eBook, The strange, icy world of Pluto to discover more about the groundbreaking mission to this distant world.