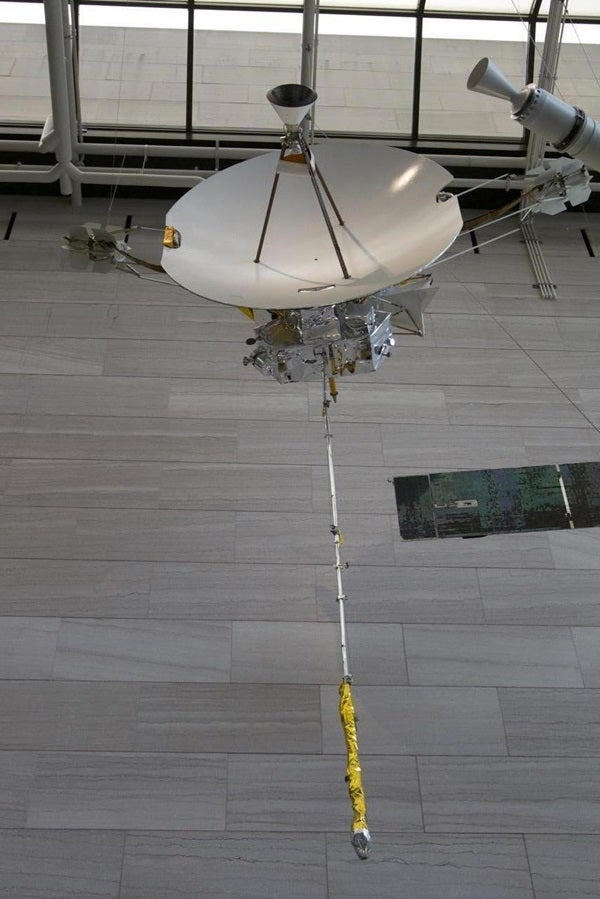

Powered by four plutonium-238 radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) each, the Pioneer spacecraft carried a plethora of scientific devices that allowed them to take photographs and make detailed measurements of the environments around Jupiter and Saturn and in the outer solar system. The Pioneers also famously carried the Pioneer plaque, with a pictorial message for any extraterrestrials who may someday encounter the craft; this would give them information as to the origin of the probes.

The Pioneers had some unique design features that allowed them to be very precisely tracked by Earth-based receiving stations. Both Pioneers were spin stabilized (which means that they rotate around a central point to keep them from wobbling or changing trajectory) and required very few course corrections that could perturb their motion. The combination of the type of transceiver aboard the spacecraft and ground-based Doppler tracking used on the missions allowed their acceleration to be tracked to an almost unbelievable accuracy of ∼ 10–10 meters per second squared (m/s2). The Voyager spacecraft, which were not spin stabilized and relied on more frequent use of thrusters, cannot be tracked to this level of precision.

The Pioneers are considered the most precisely tracked and navigated spacecraft to date. This astonishing accuracy with regards to measuring the acceleration of the Pioneers led to an unusual discovery. It was understood that the probes would slow down to some extent due to the Sun’s gravitational attraction. But while the Pioneers had reached escape velocity from the Sun and would ultimately leave the solar system, by 1980 a researcher at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory noticed the Pioneers were slowing down more than the data predicted they would. This occurred in both Pioneers, manifesting as a sunward acceleration of 8.74 ± 1.33 × 10−10 m/s2.

While this may seem like a very small difference in measured acceleration from predicted acceleration, it led to the Pioneers remaining thousands of kilometers closer to Earth per year than they should have been. The cause greatly puzzled the scientists who studied the problem. Even such a small, unexplained sunward acceleration suggested a possible breakdown in the principle of gravitation as described by general relativity.

Numerous people became interested in the problem. Why, they asked, were the Pioneers slowing down? Many factors were considered as possible causes for this unexplained deceleration, which became known as the Pioneer anomaly. Could our understanding of the fundaments of physics be flawed? Could gravitational forces from the surrounding interstellar medium that fills the space between stars be different than had been expected? Could dust produce drag on the spacecraft? Was the anomaly possibly secondary to solar radiation forces? Could our calculations regarding the exact position of Earth relative to the spacecraft be incorrect? Was something related to the spacecraft — waste heat, a faulty thruster, or a gas leak — causing the anomaly?

Beyond the theoretical problems facing researchers, another more concrete problem stood in their way: The technical information and recordings of Pioneer data needed to solve the problem were stored either on paper or on 7- and 9-track magnetic data tapes. Identifying these data sources (some of which were literally in boxes under stairwells and in dumpsters on their way to being destroyed), recovering the hardware needed to read the tapes, and converting all of this information to modern media formats was a daunting challenge on several levels, most notably the cost and manpower involved. The Planetary Society helped raise funds to help researchers like Slava Turyshev and his collaborators overcome these challenges.

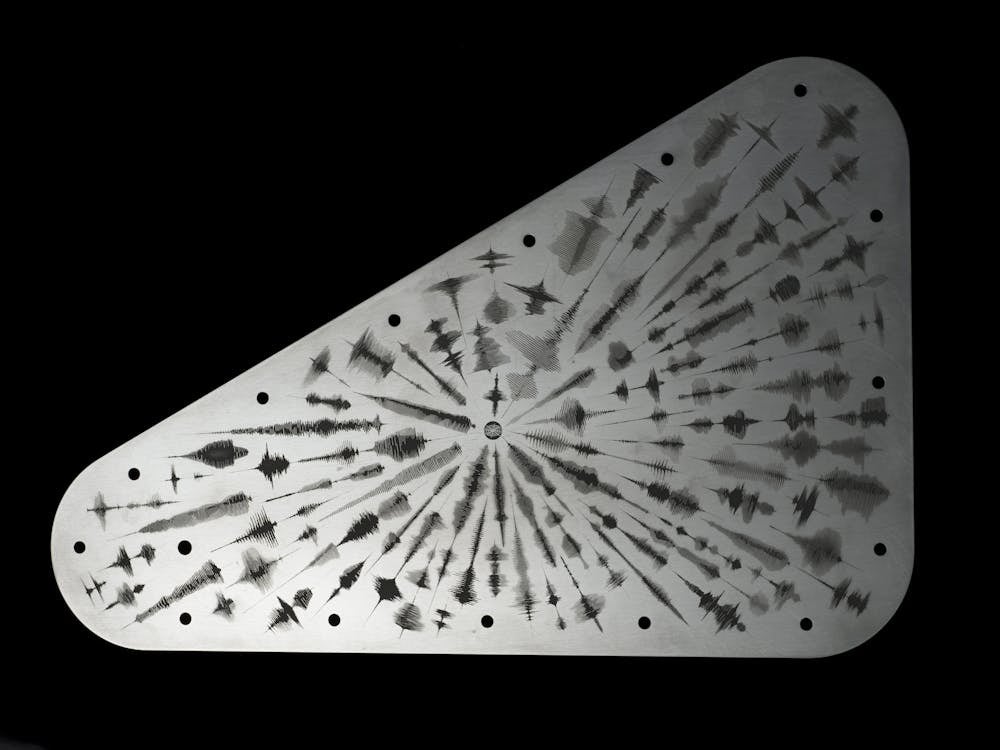

When all of these possibilities were considered, one potential cause of the Pioneer anomaly repeatedly came to the fore: thermal effects, mostly originating from the four RTGs aboard each Pioneer. To fully analyze this possibility, Turyshev and colleagues (most notably Viktor Toth) used predicted and actual thermal measurements to create a highly accurate thermal model of the spacecraft. They first modeled the effects of heating from the Sun on the trailing face of the Pioneers. Then they turned to heat sources on the spacecraft. Heat from the RTGs radiated toward the leading edge of the spacecraft, in the direction of its motion, and heat from the electronics box also primarily radiated in this same direction. This generated a sunward (backward) pressure on the entire spacecraft. As a result, the overall heating of the craft, when all factors were included, was asymmetric. Ultimately, Turyshev and colleagues concluded that radiation forces from the differential heating of the spacecraft, known as thermal recoil forces, from the RTGs and electronics were enough to explain the entire Pioneer anomaly. Additional analysis showed that the Pioneer anomaly also appears to be decreasing in intensity with time, likely as a result of the RTGs’ radioactive decay and slow decline in power output, providing further support for the conclusions reached by Turyshev.

In the end, the theory of relativity was not overthrown, our understanding of physics is not flawed, the Pioneer anomaly was explained to people’s satisfaction, and, for now, the question has been put to rest. But the story of the Pioneer anomaly shows how exacting measurements in science can generate new questions, challenge old ideas, and stimulate new ways to solve complex problems.