Instead, planetary nebulae form when a star uses up all of the hydrogen in its core — an event our Sun will go through in about 5 billion years. When this happens, the star begins to cool and expand, increasing its radius by tens to hundreds of times its original size. Eventually, the outer layers of the star are carried away by a thick 31,000 mph (50,000 km/h) wind, leaving behind a hot core. This hot core has a surface temperature of about 90,000° Fahrenheit (50,000° Celsius) and is ejecting its outer layers in a much faster wind traveling 4 million mph (6 million km/h). The radiation from the hot star and the interaction of its fast wind with the slower wind creates the complex and filamentary shell of a planetary nebula. Eventually, the remnant star will collapse to form a white dwarf star.

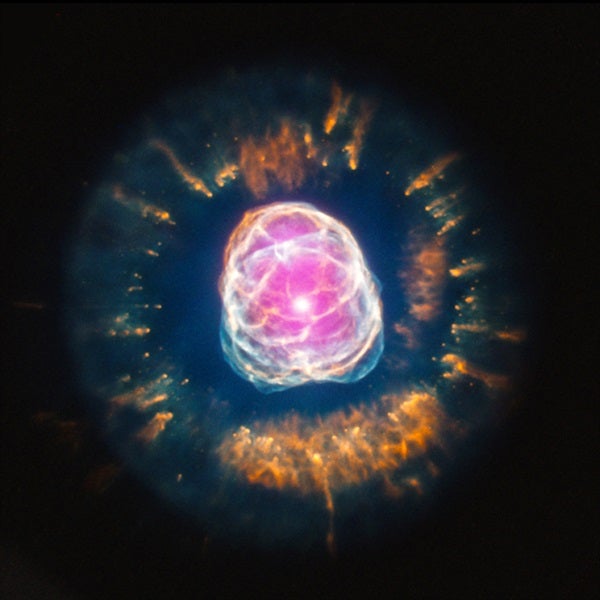

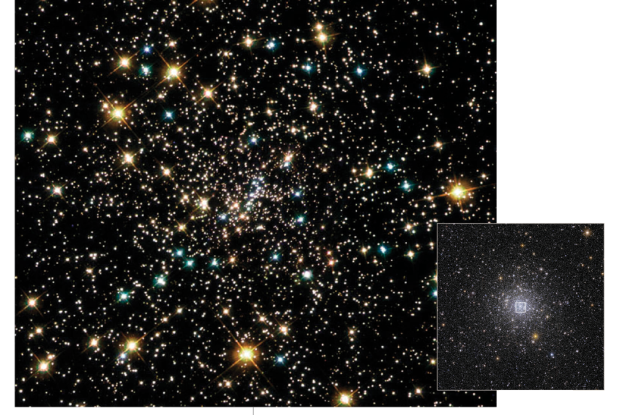

Nowadays, astronomers using space-based telescopes are able to observe planetary nebulae such as NGC 2392 in ways their scientific ancestors probably could never imagine. This composite image of NGC 2392 contains X-ray data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory in purple showing the location of million-degree gas near the center of the planetary nebula. Data from the Hubble Space Telescope — colored red, green, and blue — show the intricate pattern of the outer layers of the star that have been ejected. The comet-shaped filaments form when the faster wind and radiation from the central star interact with cooler shells of dust and gas that were already ejected by the star.

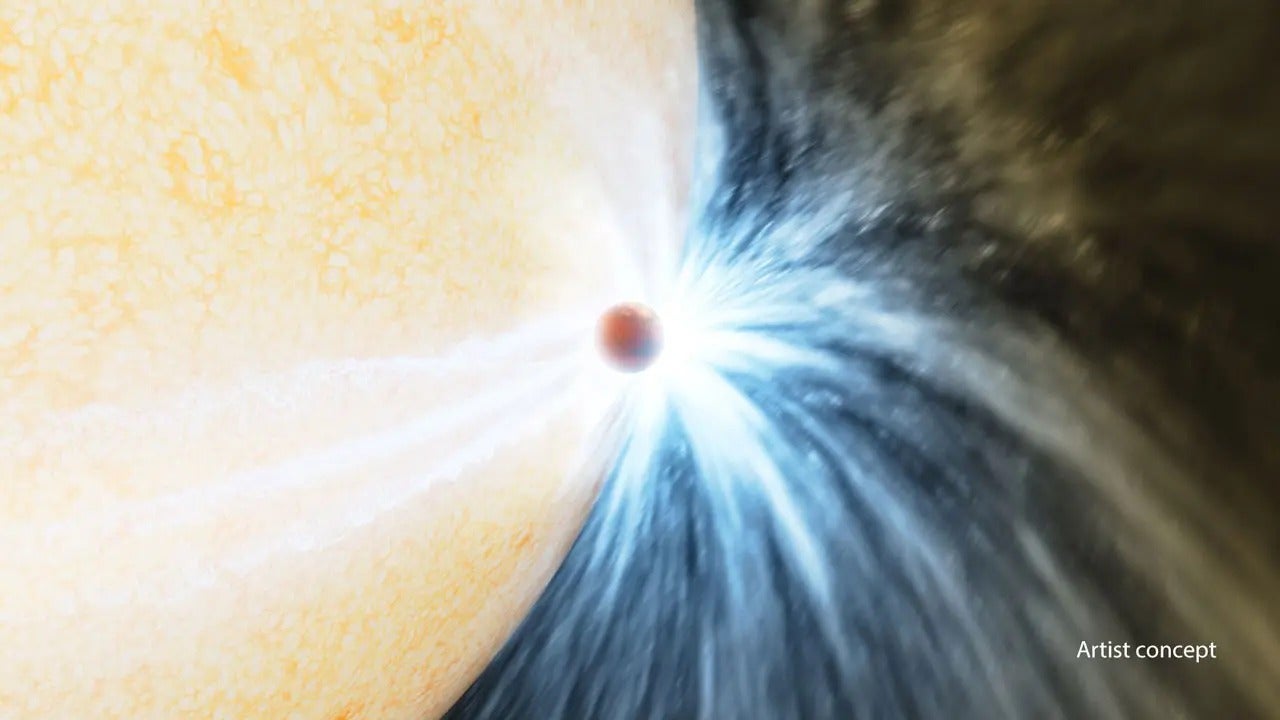

The observations of NGC 2392 were part of a study of three planetary nebulae with hot gas in their centers. The Chandra data show that NGC 2392 has unusually high levels of X-ray emission compared to the other two. This leads researchers to deduce that there is an unseen companion to the hot central star in NGC 2392. The interaction between a pair of binary stars could explain the elevated X-ray emission found there. Meanwhile, the fainter X-ray emission observed in the two other planetary nebulae in the sample — IC 418 and NGC 6826 — is likely produced by shock fronts (like sonic booms) in the wind from the central star.