What was the first planet found beyond our solar system? Astro-geeks usually cite the discovery of the Jupiter-mass planet circling the naked-eye star 51 Pegasi in 1995. But the truth is far stranger. Three years earlier, astronomers Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail announced they had found not one but two planets — and these orbited the oddest kind of star in the universe, a millisecond pulsar.

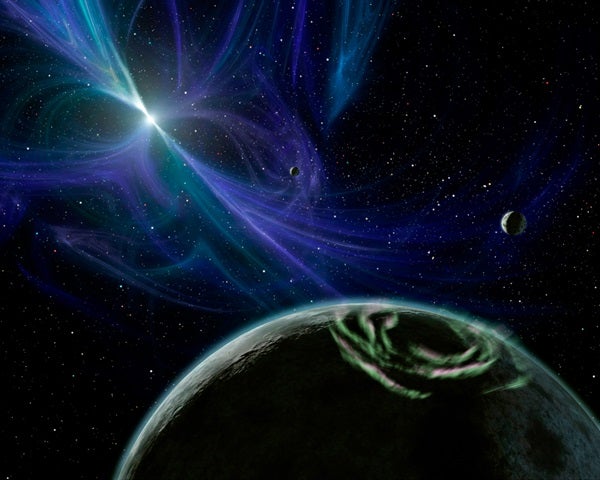

Its name is PSR B1257+12, and it lies in the constellation Virgo the Virgin at a distance of 980 light-years. It spins 161 times a second and, like all pulsars, is a neutron star, the smallest and densest visible object in the universe.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

No telescope was used in the discovery — at least not one that gathers visible light. Instead, the radio telescope in Arecibo, Puerto Rico, with its 1,000-foot (305 meters) collecting area, carefully monitored radio signals from pulsars. Electromagnetic energy streaming away from their magnetic poles sweeps around like a lighthouse beam, producing flashes with each rotation.

These super-collapsed neutron stars are always less than 20 miles (32 kilometers) wide, with wild amusement park spins of dozens or even hundreds of rotations per second. What’s valuable for astrophysicists isn’t the ultra-fast spin but the Teutonic regularity. If the rate changes, something interesting must be going on.

In 1991, astronomers detected just such a changing period in PSR B1257+12’s spin and got to work deciphering why the signals were alternately delayed and then advanced. Obviously something was yanking the tiny star back and forth in a predictable fashion. What size object, and at what orbital distance and period, would do the job? In this case, the exact fit could be achieved if this pulsar is orbited by two small nearby planets; later refinements added a third definite planet, as well as a potential ultra-teensy fourth.

Of the three definite pulsar planets, one weighs 1/50 Earth mass (not too dissimilar to our Moon), while the other two have about 4 Earth masses apiece. The “years” it takes this trio to orbit their pulsar sun last 25, 67, and 98 Earth days. And there you have the first-ever planets found since Neptune’s discovery in 1846. (We can’t count Pluto anymore now that it’s considered a dwarf planet. See object 39 on our list.)

The existence of pulsar planets took everyone by surprise. After all, a pulsar is the collapsed core of a massive sun that went kablooey in an awesome supernova — after becoming bright enough to outshine its entire parent galaxy. A supernova should obliterate any planets around it. There should be nothing left, not even dust.

Yet here they are, orbiting in well-behaved near-circular paths. No doubt these planets are remnants — on-sale damaged goods. They each must have started out as giant Jupiter-class gas objects, and the intense explosion blew most of their bodies away until only their rocky cores remained. Frankly, how even those withstood a nearby supernova blast is no small mystery to try and explain. They simply don’t build them like that anymore.

Some theorists argue that these planets must have formed after the supernova blast, but there are major troubles making sense of that. The neat ordering of these coplanar worlds (they all lie in the same pancake-like flat plane) strongly suggests they were created from scratch in an original protoplanetary disk, like the genesis of our solar system. If so, their survival and continued existence is indeed a puzzle.

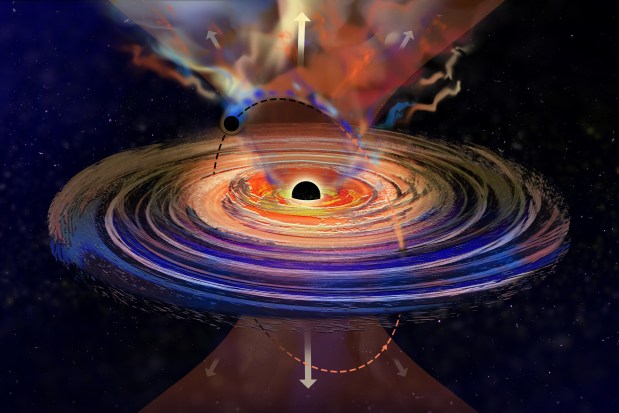

In 2000, astronomers found an even more remarkable pulsar planet, but this time in the constellation Scorpius. Pulsar PSR B1620–26 is a binary star in the beautiful globular cluster M4 right near Antares, 12,400 light-years away. The system consists of two collapsed stars in a tight orbit — a pulsar 16 miles (26 km) wide and a white dwarf the size of Earth. The planet circles them both! To clear them in a stable fashion, its orbit is large, and its “year” is a period of exactly one Earth century. Strange, or what?

Since globular cluster M4 is ancient, with all its stars and planets born together more than 12 billion years ago, scarcely a billion years after the Big Bang, this pulsar-orbiting world

is also the oldest planet ever discovered. It was celebrating its

8 billionth birthday when our Sun first clicked on and while Earth was still a ball of fiery goo.

Pulsar planets are not good places to raise a family. Their property values are low. From their surfaces, the tiny pulsar they orbit, though sometimes quite nearby, is a speck, a dot with no size, even if much too brilliant to look at. It delivers lethal X-rays and gamma rays along with stark visible light. Radiation is such a mortal hazard that no life could possibly be around to enjoy the strange panorama.

We’ll have to do the contemplating from here.