Stuster could never have guessed that his future career path would land him at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center. After college, he pursued a doctorate in anthropology, hoping to study hunter-gatherers in Borneo. He instead wound up writing his doctoral dissertation on commercial fishermen in Santa Barbara, California. And in 1982, shortly after joining a behavioral sciences and human factors research firm called Anacapa Sciences in Santa Barbara, he began working with NASA.

“When the astronauts know I’m an anthropologist … they open up,” explains Stuster, now president and principal scientist at Anacapa. He notes that, unlike the psychologists or physicians who evaluate astronauts, he can’t expel anyone from the mission roster.

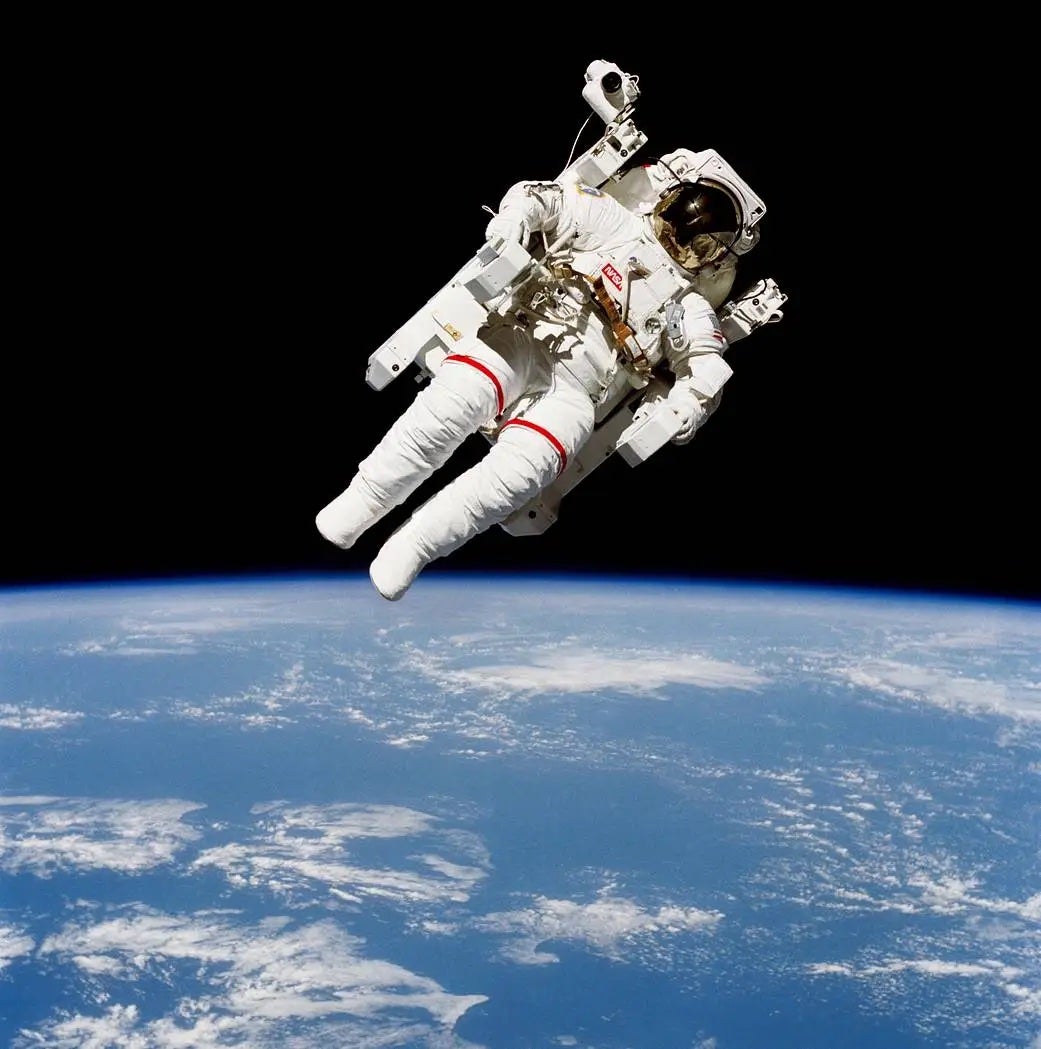

Over his career, Stuster has helped forecast potential issues, identify real problems — such as when shuttle refurbishments were delayed by poor communication — and made suggestions that influenced the design and activities on the International Space Station (ISS). As NASA turns its focus toward Mars, he recently completed a report identifying all the tasks interplanetary explorers must be ready for—many of which NASA hadn’t yet considered.

The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Your first space project was in 1982, when NASA called in Anacapa Sciences to help make the refurbishment of space shuttles safer and more efficient. How did it feel to arrive at Cape Canaveral during the early shuttle program?

We started with a tour of the shuttle Columbia. At each level, we would stop and look at this incredible machine, this spacecraft. I let the others walk ahead of me so that I could pinch myself. It was awe-inspiring to be that close. I was proud to be a member of the species that could build such a complicated machine.

I wanted to remain involved. During this job, I noticed a sign on a door that said, “Space Station Working Group.” I thought, Wow, NASA’s actually thinking about building a space station? Maybe that’s my ticket.

In the absence of a real space station, I proposed to study conditions on Earth that are in various ways similar to a low Earth orbit space station: Antarctic research stations, submarines, oil platforms, things like that.

That research led to your 1986 report on living in space. You provided a variety of recommendations, including daily changes of underwear and regular mental health monitoring. How did NASA respond?

The report was a really big hit among the engineers who were designing the International Space Station. They liked it because it was based on real-world conditions. Several of my recommendations made it to the ISS, such as facilities that enable the whole crew to eat together.

Early on, astronauts would complain about having to do inventories of lightbulbs and underwear and stuff. It helps to divide tedious housekeeping tasks as evenly as possible. Now, since NASA has enlarged the crew size, these tasks are spread over a wider group.

Plus, when astronauts get on the ISS, they are confronted with this phenomenon called “space fog” or the “space stupids.” They don’t think as quickly as they did on the ground. This may be a result of fluid building up in their head so they feel stuffed up, too little sleep, busy schedules, low gravity, and high levels of carbon dioxide. They get behind schedule and put things away quickly, so it’s harder to find tools the next time. To adjust, NASA should schedule sufficient time for all tasks.

When you’re living in isolation and confinement, every little annoyance is magnified. Astronauts need to do the same things we do on Earth to get along, like refilling the toilet paper or putting the seat down after using the commode. It’s really aggravating when you go to use the zero-gravity toilet and the supplies you need aren’t there. Or the person before you left the solid-waste reservoir full, which means you can’t use the toilet until you’ve emptied it. Keeping up morale, in many ways, is just a matter of being as considerate as possible. More than considerate: Avoid being annoying in any way.

The three most recent NASA Mars mission plans did not include a pilot, assuming piloting and navigation would be automated or directed from Earth. I seriously doubt that you would get professional astronauts to go on a mission with no human pilot, only a computer, meaning they wouldn’t survive if the computer and communications failed.

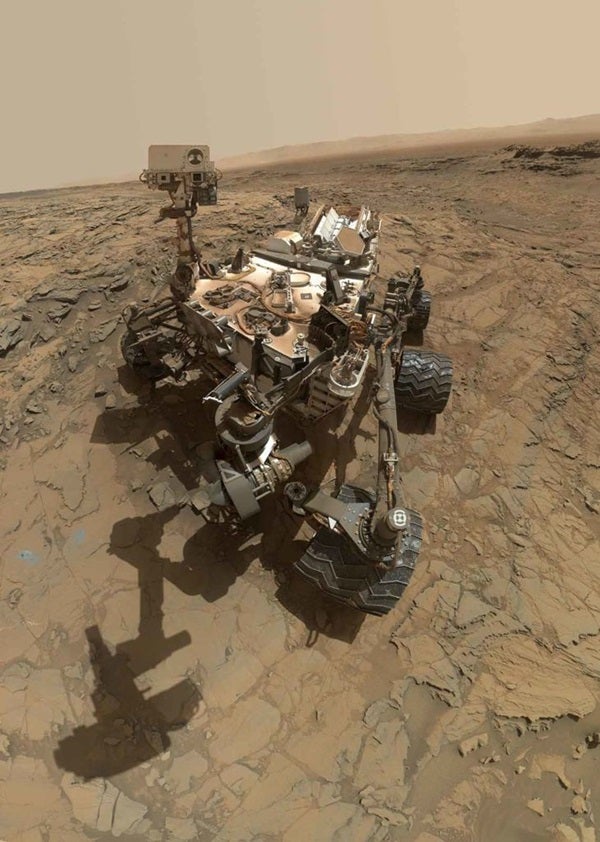

NASA assumed Mars explorers would use the standard, gas-pressurized space suit. But if you get a wheel of your rover stuck in the loose sand and rocks on the Martian surface—as happened to the character Mark Watney in the film The Martian—you have to kneel to dig it out. That would be impossible wearing a gas-pressurized suit. They’ll need a mechanical pressure suit, or some sort of hybrid, that enables more flexibility.

In that new report, you defined key jobs that ought to be spread among the Mars crew: leader, pilot/navigator, geologist, biologist, physician, mechanic, electrician, and computer specialist. Who would be on your personal dream team to Mars?

Ellen Ripley played by Sigourney Weaver in Alien. Wouldn’t you want Sigourney Weaver? Mark Watney played by Matt Damon. Joe Turner played by Robert Redford in Three Days of the Condor—not a space film, but the characters that Redford plays tend to be calm and deliberate. John Wick played by Keanu Reeves in the John Wick series, in case the crew encounters hostile aliens, and because Reeves seems to be a kind and generous person—a perfect comrade during prolonged isolation and confinement.

Do you see any role for anthropologists as crew members on future expeditions?

I doubt it, not unless the first mission discovers there’s an alien culture.

I applied to be an astronaut, for many years, but I wasn’t selected. I would have gone in a heartbeat.

This work first appeared on SAPIENS under a CC BY-ND 4.0 license. Read the original here.