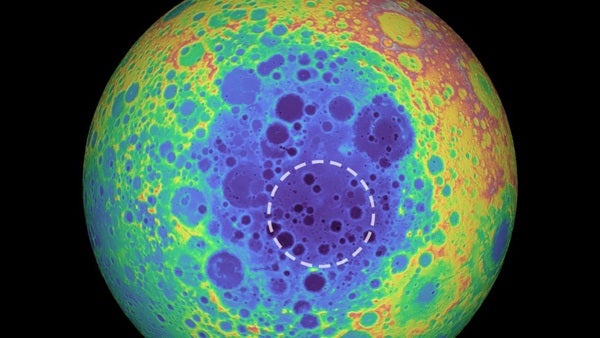

Astronomers led by Peter B. James from Baylor University discovered the hidden feature by combining data from NASA’s GRAIL lunar orbiter mission and the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter to look at where regions of high gravity — and therefore mass — overlap with surface features like craters. They found a giant mass weighing down the floor of the South Pole-Aitken basin by more than half a mile (0.8 kilometer).

“Imagine taking a pile of metal five times larger than the Big Island of Hawaii and burying it underground. That’s roughly how much unexpected mass we detected,” James said in a press release.

Present from the Beginning

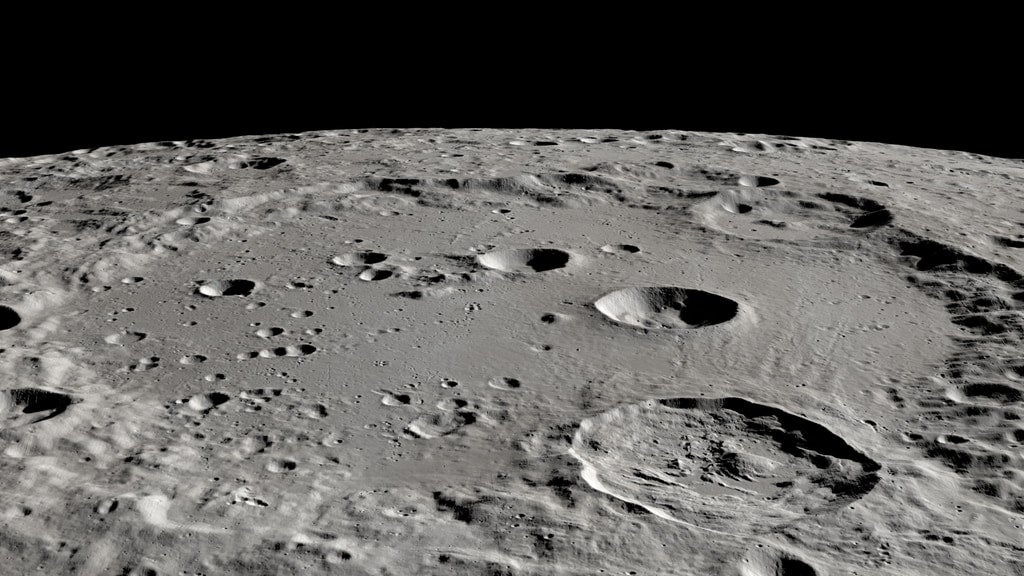

James and his colleagues suggest that one possible explanation for the underground material is that it’s the remains of a massive asteroid that slammed into the Moon soon after its formation, causing the giant impact crater still visible today. The South Pole-Aitken basin is the oldest crater on the Moon — it’s covered with newer, smaller impact scars, but still clearly visible.

The basin is one of the largest and best-preserved craters in the entire solar system, covering nearly a quarter of the Moon’s surface. The asteroid that made the impact would also have been large, perhaps 100 miles (160 km) across.

James’ research suggests that the nickel and iron that made up the asteroid could have stayed embedded in the Moon’s middle layers, rather than sinking into the denser core over the eons. That would yield something like the large mass they see today, which sits underneath the same area it impacted and blew apart so long ago. James’ team published their research April 5 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Alternatively, the mass might be a dense region caused by the Moon’s magma ocean solidifying as our satellite cooled and aged.

The Chinese lander Chang’e-4 and its Yutu-2 rover are currently exploring the Von Karman crater within the South Pole-Aitken basin, and NASA also wants to target the South Pole for future exploration. There’s still much to learn about the ancient and complex geology of the area, which marks a key event in the Moon’s tumultuous history.