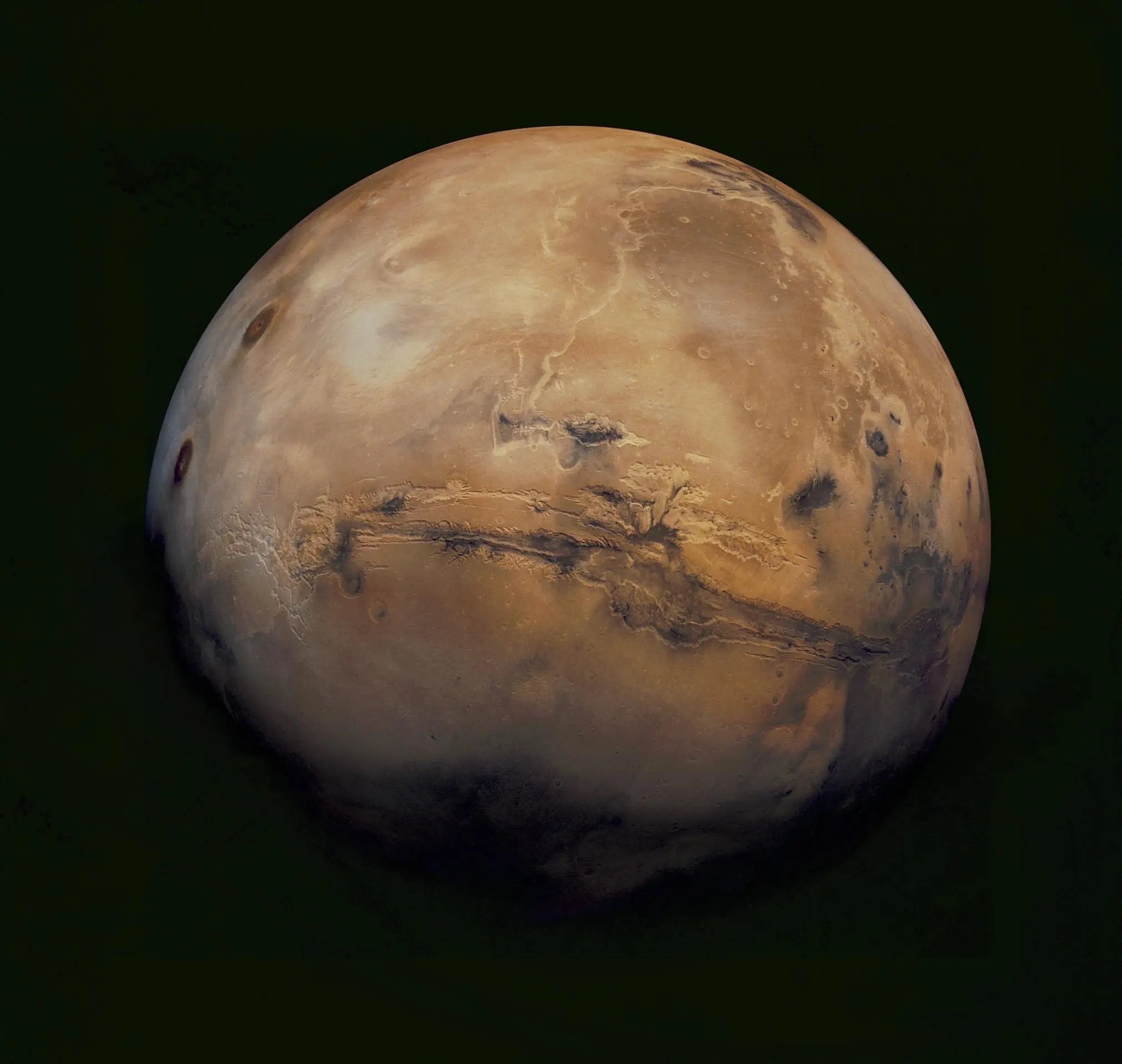

Planetary scientists at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco today announced startling discoveries on Mars. Using data from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), a team of planetary scientists including Jack Mustard of Brown University, Roger Phillips of Washington University, and Ken Herkenhoff of the U.S. Geological Survey discovered layers of ice-rich deposits near the martian poles. Variations in the thickness of these layers will enable the scientists to trace the history of Mars’ atmosphere back in time millions of years.

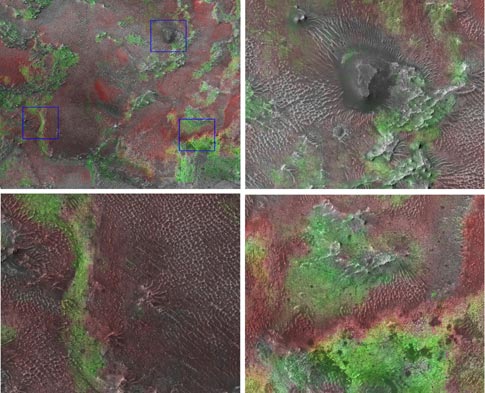

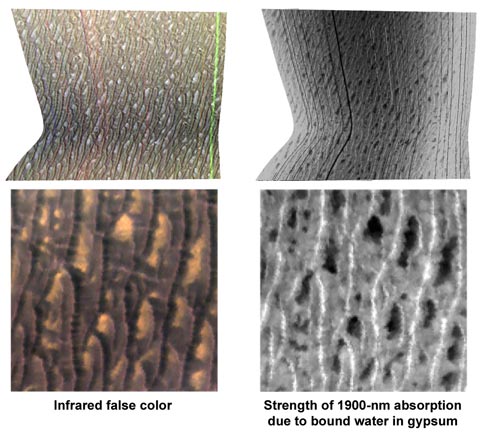

The team also found widespread sand dunes composed of olivine-rich sand, and surrounding terrains rich in gypsum and clay minerals show many areas of Mars formed in past water-rich environments.

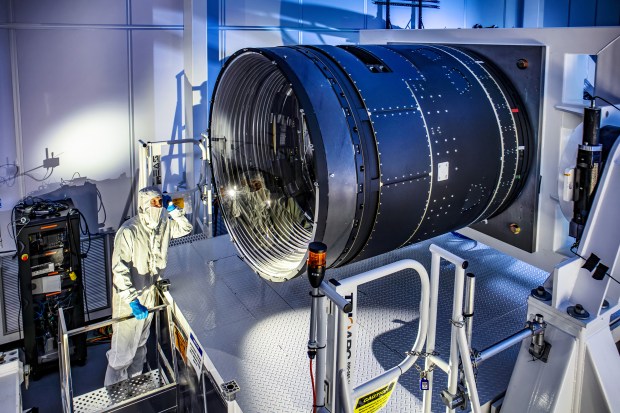

The new studies resulted from multiple MRO instruments working in unison. “The combination of instruments on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter is such a great advantage,” says Mustard. He oversees the analysis of data from the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), an instrument used recently to map phyllosilicates (clay minerals) in the region of Nili Fossae.

“It’s like stumbling onto a gigantic deposit of olivine beach sand you might see in Hawaii,” says Mustard. The great abundance of gypsum (calcium sulfate) in the area of Olympia Undae also calls for large amounts of past water to form.

Another of MRO’s instruments, SHARAD (shallow subsurface radar), observed polar layered deposits that hold a record of Mars’ past climate. “These deposits record relatively recent climate variations on Mars,” says Herkenhoff, “like recent ice ages on Earth.”

At Mars’ north pole, new results are exciting the science team. “The radar is penetrating through the entire thickness of these deposits,” says Phillips, “and revealing the fine-scale internal layering.” By analyzing radargrams, Phillips sees a long history of deposition in the layers.

“We are seeing the entire climate history in these images, from orbit,” says Herkenhoff. The scientists are imaging faults and pits along the polar cap, seeing immense evidence of windblown erosion. The images reveal person-sized to house-sized blocks of ice.

In future weeks, SHARAD will look for subsurface aquifers, including the active gullies with flowing water discovered over the last few weeks. “In order to detect flowing water under the surface,” says Phillips, “aquifers would have to be mostly water, and flowing in relatively new surfaces. We will definitely be looking.”

Of the amazing mineralogy discovered in the newly announced results, Mustard says, perhaps an enterprising jewelry company will one day find its way to the Red Planet. “You could put your hand down into these dunes and pick up some really nice peridot,” he says, referring to the gem grade of olivine. “And we already know there’s lots of pretty hematite there.”

Mars, we’re finding, has some pretty interesting mineralogy after all.