So, is your telescope ready? Our target, the water snake Hydra, is a fearsome creature — both mythologically and astronomically.

Hydra is the largest of the 88 recognized constellations; with an area of 1,303 square degrees, it covers about 10 times as much sky as Triangulum. Hydra winds its way across part or all of eight zones of right ascension — far too much territory for a single observing session. What to do? Here’s a tactic I learned during my decades as an avid freshwater fisherman.

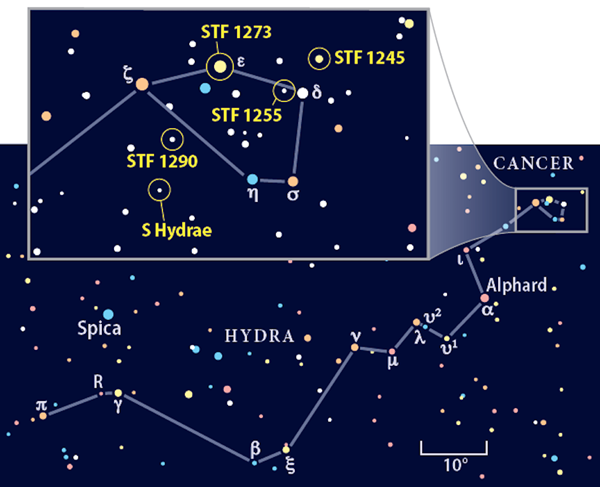

Before heading out to fish, I look at a map of the lake and single out a promising area — perhaps a bay near an inlet. I concentrate on this one spot, saving other parts of the lake for future trips. The same approach can be used for covering large constellations, referring to a star atlas to zero in on a promising section. For instance, if I’m in a double star mood (and when am I not?), Bruce MacEvoy and Wil Tirion’s Double Star Atlas identifies several binaries near a distinctive group of stars that forms the head of Hydra. The area covers only about 20 square degrees, so I’ve essentially turned a vast lake into a small pond.

Returning to Hydra, train your telescope on STF 1255, ½° east of the 4th-magnitude star Delta (δ) Hydrae. Fainter than STF 1245, it’s nevertheless bright and wide enough (magnitudes 7.3 and 8.6, separation 26″) for an easy split in a small-aperture scope like a 3-inch f/10 reflector. Both are G-type stars, but the colors might not be so obvious in such a small instrument.

The next pair will require a bigger boat, er, telescope. One of Struve’s doubles (STF 1273) is better known by its Greek moniker, Epsilon (ε) Hydrae. The brighter component, of magnitude 3.5, is attended by a magnitude 6.7 companion a mere 2.9″ away. A 5-inch scope should split this pair, but you’ll still need an evening of steady seeing and an eyepiece that magnifies 150x or more.

If you’re able to split ε Hya, move on to an even more difficult challenge, STF 1290. This magnitude 7.4 and 9.2 duo is located about 2.5° southeast of ε Hya. The two stars are separated by just 2.8″. If 150x doesn’t work with a 5-inch telescope, try 200x.

Double stars, however, aren’t the only fish in the Hydra lake. A variable star, S Hydrae, lies 1.5° south and slightly east of STF 1290. S Hya is a long-period variable (LPV). LPVs are also called Mira-type variables after the prototype, the star Mira (Omicron [ο] Ceti) in the constellation Cetus. Most are red giants that pulsate in somewhat regular cycles, changing brightness as they beat. S Hya cycles from an average maximum brightness of magnitude 7.3 to an average minimum of 13.3 and back again once every 8.5 months. The last max was in late September of last year; the next should occur sometime in mid- to late May this year. To monitor the changes, check out S Hya every seven to 10 days using a chart, like the one on the American Association of Variable Star Observers’ website, that shows the magnitudes of nearby stars.

Given its astounding size, there are many other parts of Lake Hydra that any angler/astronomer can explore. Next session, we might just migrate south to check out the open cluster M48 and the double stars STF 1270 (magnitudes 6.9 and 7.5, separation 4.7″) and 17 Hydrae (magnitudes 6.7 and 6.9, separation 4.1″).

Questions, comments, or suggestions? Email me at gchaple@hotmail.com.

Next month: What visual double star has a companion that circles its main star once each day? Clear skies!