The Sun is an ordinary star. It bathes the solar system with light and heat, making life possible on Earth. It’s as regular as clockwork, and it sets our daily life cycles in conjunction with Earth’s spin. Little wonder ancient peoples revered the Sun as a god. Yet the Sun will not always be steady and reliable. Billions of years from now, the Sun’s finale will turn Earth — and the entire inner solar system — into a very nasty place.

At 4.6 billion years old, the Sun is about halfway through its life. Its adulthood, called the main sequence phase, lasts 10 billion years. When the Sun runs out of hydrogen fuel, it must generate energy by fusing heavier elements.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

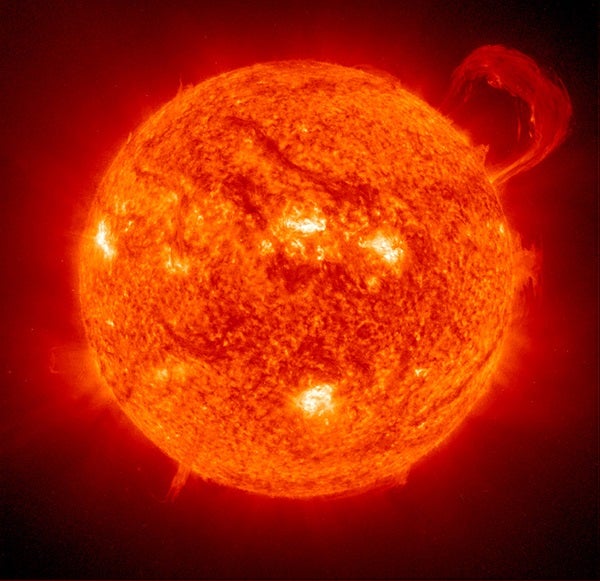

At that point, its main sequence phase is over. In one of the most peculiar transformations we know of, the Sun’s helium core, about the size of a giant planet, will contract and heat up. And, in response, the Sun will expand by 100 times.

The swollen Sun will consume the planets Mercury and Venus — and possibly Earth as well. Astronomers watching from another solar system would classify this bloated version of our Sun as a red giant.

With the Sun’s transformation into a red giant come new types of fusion reactions. An outer shell will fuse hydrogen as the byproducts fall inward, further compressing and heating the core. When the core reaches 180 million degrees F (100 million degrees C), its helium will ignite and begin to fuse into carbon and oxygen.

The Sun will shrink somewhat, but, after a time, and for 100 million years, it will again expand. It will then brighten significantly as it plunges toward the end of its helium-burning phase, when vigorous outflows called stellar winds strip the Sun’s outer layers. This will lead to the Sun’s final life phase — a cyclical, gentle shedding of gas into what astronomers call a planetary nebula.

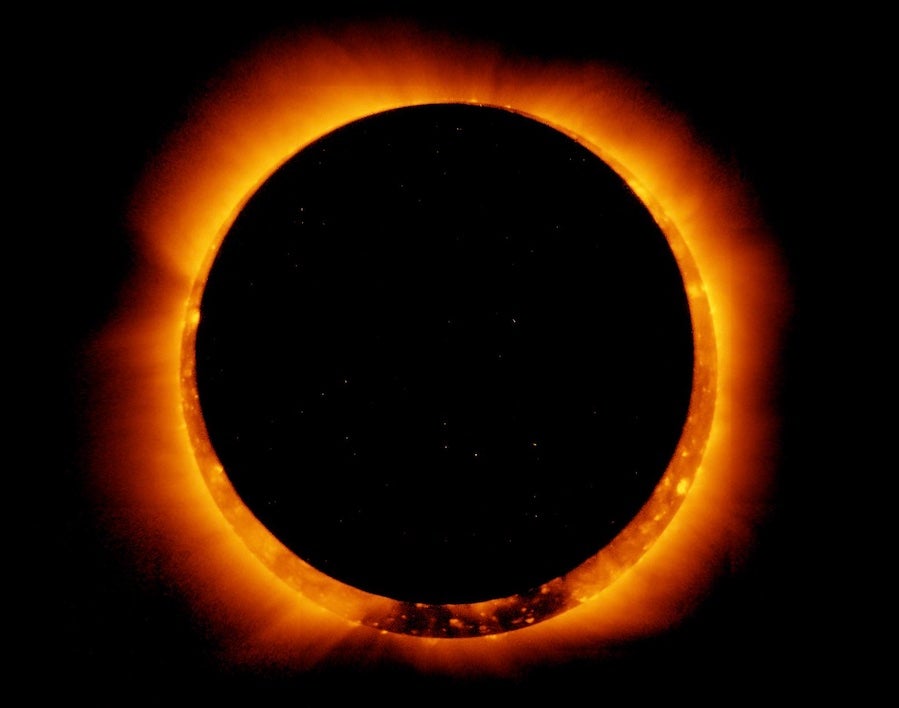

A question Stern and other planetary scientists are asking: Will the outer worlds with newfound water evolve life in the relatively brief intervals they have to do so? The liquid water on these worlds might exist for only a few hundred million years. After that, the Sun’s luminosity will dim to the point where these new water worlds will permanently refreeze. Hydrocarbons that could contribute to life’s emergence are already there, though. So, it’s possible that, in its death throes, our Sun may seed new life.

Some 10 billion red giants blaze today in the Milky Way Galaxy. Among all of these aged stars, might some have spawned new life on worlds that remained frozen during the stars’ main sequence phases? It’s possible, say astronomers, but only time — and a whole lot more research — will tell.