Q: How can a quark-antiquark interaction make an electron? A quark is an elementary particle and is not made of an electron and other particles.

A: You are absolutely correct that a quark and an antiquark are fundamental particles, yet they can interact and form new ones. When they meet, they intermingle and form a “virtual photon” — a photon that lives for only a very short time. A photon is another name for a particle of light, like those that make up what you see from a light bulb or those that compose higher-energy X-rays.

A virtual photon can violate some laws of physics, as long as its lifetime is less than a value determined by the photon’s energy and a physical constant (called Planck’s constant). This “loophole” is related to something called Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. A virtual photon briefly lives and then decays into new particles.

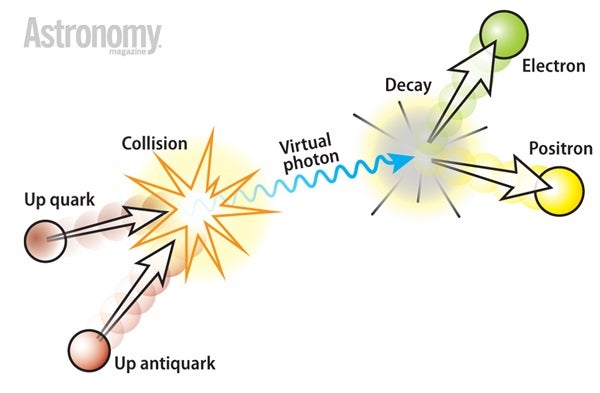

Here is one simple example of a quark-antiquark interaction:

1. An up quark (electric charge +2/3) interacts with anup antiquark (charge –2/3).

2. They form a virtual photon, which has no charge but does have a mass. (A photon with mass is a violation of the laws of physics.)

3. The virtual photon decays within the time limit allowed by Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, sometimes into an electron (charge –1) and an anti-electron, called a positron (charge +1).

A quark and antiquark that annihilate each other can form other quark pairs and other elementary particle pairs such as a muon and an anti-muon. Nature provides many other ways that quarks can combine.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory,

Berkeley, California