Key Takeaways:

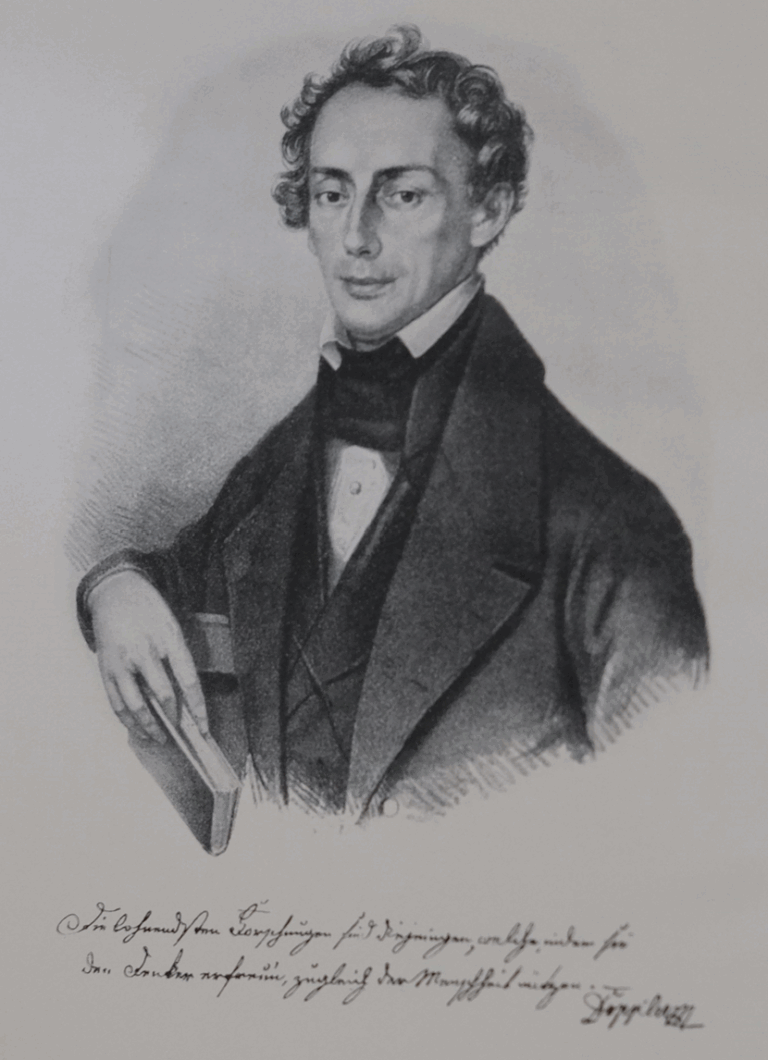

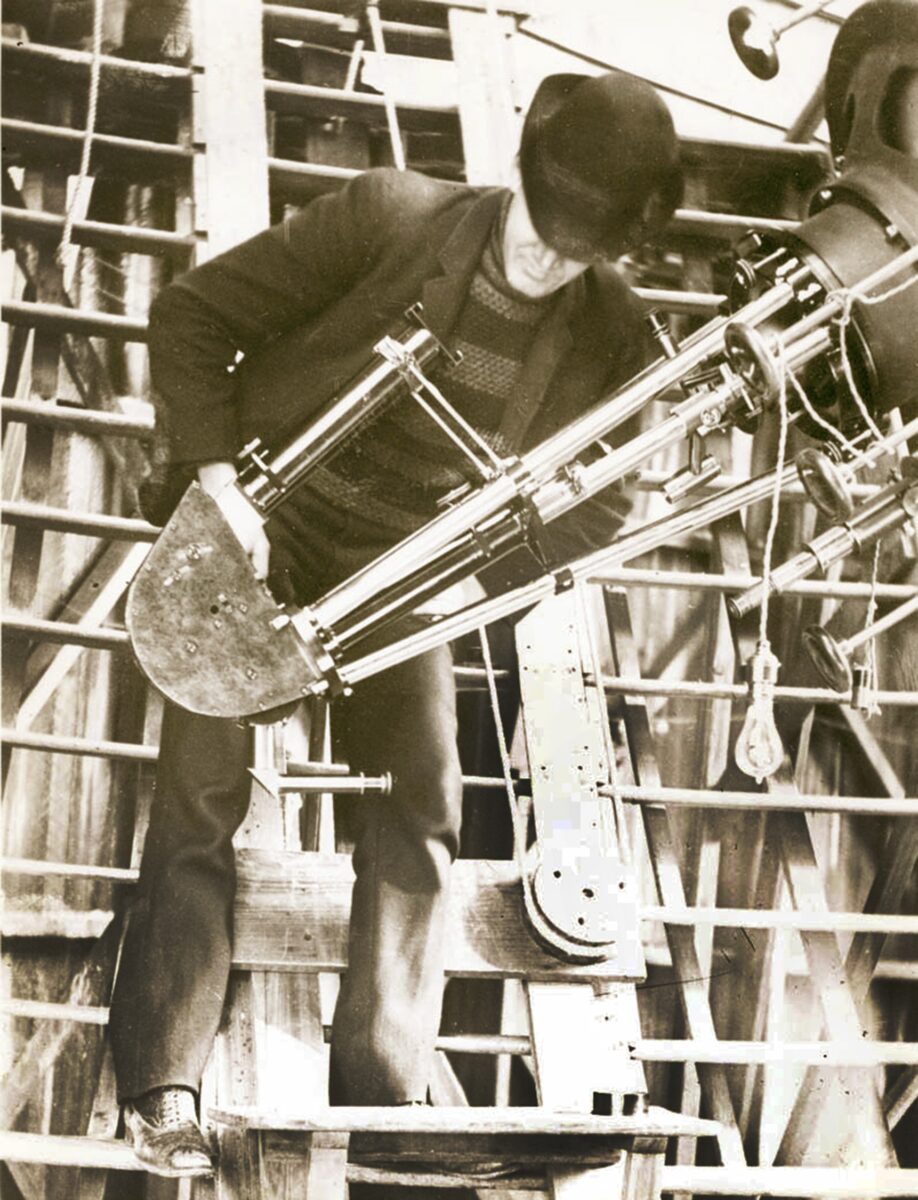

- Vesto Melvin Slipher began his 53-year career at Lowell Observatory in 1901, progressing from a staff astronomer to director by 1926, a role he maintained until his retirement in 1954.

- In 1912, Slipher successfully measured the radial velocity of the "Andromeda Nebula," determining it was approaching Earth at an unprecedented speed of 300 kilometers per second.

- By 1914, his observations extended to 15 "spiral nebulae," demonstrating that nearly all exhibited high recessional velocities, thereby establishing the empirical basis for an expanding universe.

- Slipher's velocity measurements were a critical component of Edwin Hubble's 1929 derivation of the velocity-distance relationship for galaxies, collectively advancing the understanding of cosmic expansion, galactic nature, and extragalactic distances.

Vesto Melvin Slipher was born on a farm in Mulberry, Indiana, on Nov. 11, 1875. He graduated from high school, taught briefly at a country school, and then enrolled at Indiana University in Bloomington. In 1901, one of Slipher’s professors, Wilbur Cogshall, persuaded the founder of the fledgling Lowell Observatory to bring the young astronomer on staff. Percival Lowell was reluctant; as far as he was concerned, the association would be temporary. In the end, however, Slipher would stay at the observatory for 53 years. In 1915, he became assistant director, and when Lowell died the following year, Slipher became acting director and then director by 1926. He served as the observatory’s chief until retiring in 1954 at age 79.

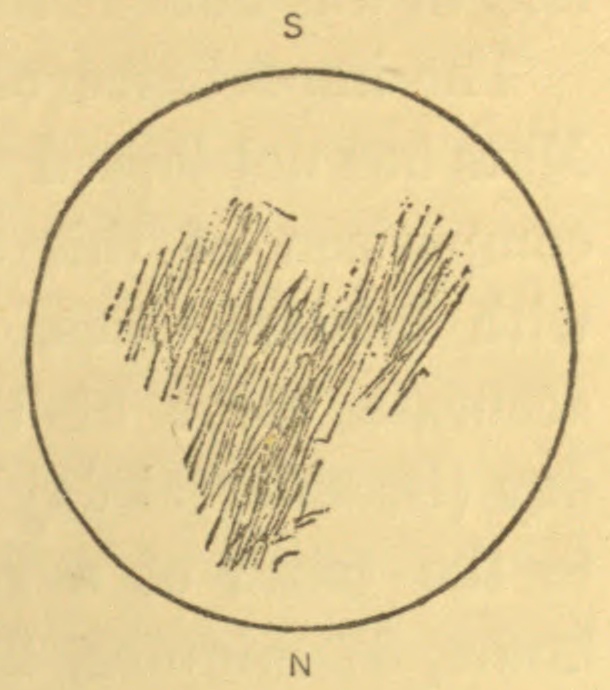

In the fall of 1912, Slipher recorded a plate of the “Andromeda Nebula” that he felt was sufficiently good to obtain its radial velocity. No radial velocities of nebulae were known at that time. He recorded better plates in November and December 1912, and measured the plates over the first half of January, finding that the nebula was moving three times faster than any previously known object in the universe. On Feb. 3, 1913, he wrote to Lowell that the Andromeda Nebula was approaching Earth at the unheard-of velocity of 186 miles per second (300 kilometers per second), still an accurate value. “It looks as if you had made a great discovery,” wrote Lowell. “Try some other spiral nebulae for confirmation.”

By the 1914 American Astronomical Society meeting, Slipher was able to announce results for 15 spirals. Nearly all were receding at high velocities. Three years later, Dutch astronomer Willem de Sitter theorized that the universe is expanding. It was Slipher’s observations of the so-called spiral nebulae that established this fact. And then in 1923 came Hubble’s discovery of the nature of galaxies. By 1929, Hubble derived his crucial velocity-distance relationship for galaxies, using, as Hubble wrote Slipher, “your velocities and my distances.” Slipher and Hubble had together uncovered the expanding universe, the nature of galaxies, and a way to measure extragalactic distances.