Key Takeaways:

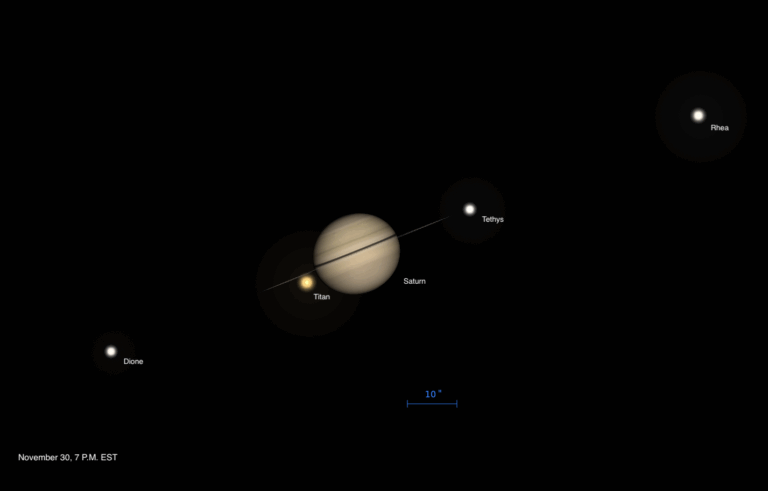

- Early December evenings feature Saturn in the northwest, displaying diminished brightness attributable to its greater distance from Earth and a narrowing of its ring system; telescopic observations reveal distinct ring details and several moons.

- Later in the evening, Jupiter becomes prominent in the northeast, moving retrogradely towards its January opposition, with telescopic views exposing atmospheric zones, belts, and its four Galilean satellites.

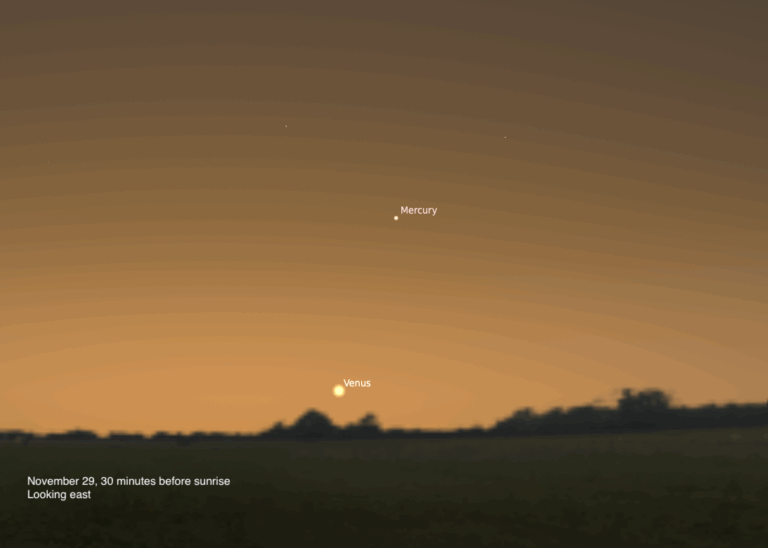

- Mercury is observable low in the eastern morning sky early in the month, reaching greatest elongation on December 7th, while Venus and Mars are unobservable, being situated on the far side of the Sun.

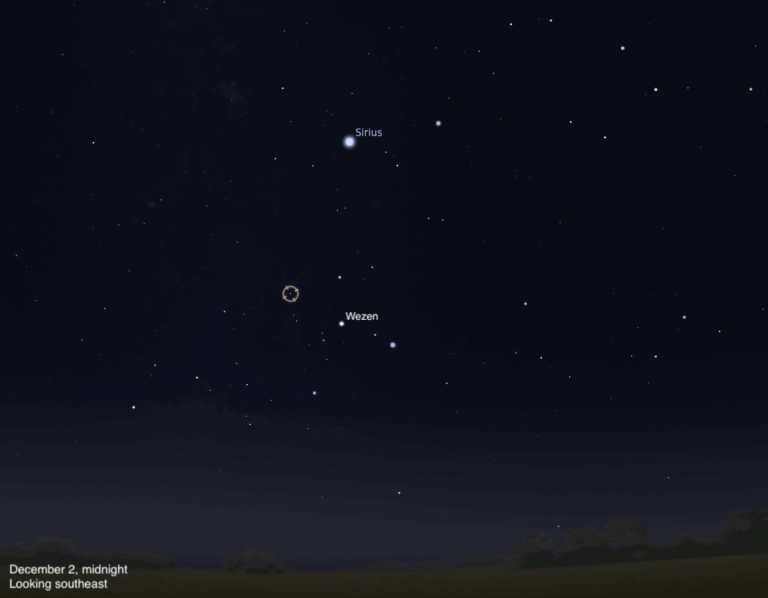

- The Southern Hemisphere's evening sky offers views of prominent bright stars such as Sirius and Orion's luminaries, alongside significant deep-sky objects including the extragalactic Tarantula Nebula (NGC 2070) and Milky Way globular clusters 47 Tucanae (NGC 104) and NGC 6752, which are well-positioned for telescopic study.

As the final month of the year begins, early evenings offer just one naked-eye planet. Fortunately for us, that lone world is Saturn. The ringed planet lies high in the northwest as twilight fades, tucked among the faint background stars of northeastern Aquarius the Water-bearer.

Saturn shines at 1st magnitude, brighter than any nearby star but noticeably fainter than it was at opposition in September. That’s partly due to its greater distance from Earth, but more so to the narrowing tilt of its rings. At opposition, the ring system tilted 1.8° to our line of sight; in mid-December, that value falls to 0.6°. When the rings appear wide open, as they will in 2031 and 2032, Saturn reaches magnitude –0.5, some 2.5 times brighter than it does this year.

A telescope delivers a fascinating view of the planet. The razor-thin rings span 40″ at midmonth and encircle a disk with an equatorial diameter of 18″. The reduced glare from the rings also makes it easier to spot Saturn’s moons. Eighth-magnitude Titan is always easy to see, and 10th-magnitude Tethys, Dione, and Rhea are only a bit more difficult. You might even catch two-faced Iapetus, which glows at 11th magnitude when it passes 1.1′ due south of the planet Dec. 6.

Later in the evening, Jupiter rises in the northeast. It shines brilliantly at magnitude –2.6 to the upper right of Gemini’s two brightest stars, Castor and Pollux. The giant planet moves slowly westward (retrograde) against the backdrop of the Twins as it heads toward opposition in January.

The best views through a telescope come well after midnight, once Jupiter climbs higher in the sky. Even the smallest scopes show plenty of detail in the gas giant’s bright zones and darker belts. The planet itself spans 46″ in mid-December. Also keep an eye out for Jupiter’s four bright Galilean satellites: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

As morning twilight starts to paint the sky, look for Mercury low in the east. The innermost planet reaches greatest elongation Dec. 7, when it lies 21° west of the Sun and stands 7° high 30 minutes before sunrise. This isn’t the best Mercury apparition because the ecliptic currently makes a shallow angle to the eastern horizon at dawn.

Plan to target the inner world with your telescope early in the month. On the 1st, Mercury spans 8″ and shows a pretty 36-percent-lit crescent.

The other two naked-eye planets remain out of sight all month. Venus and Mars both lie on the far side of the Sun and are lost in our star’s glare.

The starry sky

The eastern evening sky features several bright stars at this time of year. The sky’s brightest star, magnitude –1.4 Sirius, lies due east as the last vestiges of twilight fade away. The second-brightest star, magnitude –0.6 Canopus, appears about 35° to Sirius’ upper right. And Orion’s two luminaries, Betelgeuse and Rigel, reside some 25° to Sirius’ upper left.

Unfortunately, the southern sky’s most famous constellation, Crux the Cross, hangs low in the south on December evenings. It even dips below the horizon for observers closer to the equator. Yet three of the sky’s finest deep-sky objects stand out nicely in the south after darkness falls. Let’s tackle them by moving clockwise around the South Celestial Pole from Crux.

About seven hours of right ascension to the east (left) of Crux lies a true standout: the Tarantula Nebula (NGC 2070). It shows up to the unaided eye under a clear dark sky, but it truly shines when viewed through a telescope. In either case, averted vision helps considerably. The most remarkable aspect of this object is that it doesn’t even belong to the Milky Way Galaxy. It resides in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy to our own located 160,000 light-years away. As the hour grows later these December nights, the Tarantula climbs higher.

Head another five hours of right ascension clockwise around the pole and a little closer to it to find the sky’s second-best globular cluster — at least, in my opinion. Cataloged as 47 Tucanae and NGC 104, this 4th-magnitude object appears as a fuzzy ball to the naked eye under a reasonably dark sky. Although it seems to reside on the outskirts of another nearby galaxy, the Small Magellanic Cloud, it belongs to the Milky Way. The cluster’s nicest feature is its pronounced central condensation that shows up well through modest telescopes. Such instruments resolve many of the globular’s outer stars, but the central region remains a bright round sphere.

Southern Hemisphere observers really are spoiled when it comes to viewing globular clusters. The two best (Omega Centauri ranks at the top of the list) both lie well south of the celestial equator. And because they stand on opposite sides of the celestial pole, at least one is always well placed in the sky.

Continue your clockwise sweep around the pole and you’ll eventually arrive at Pavo the Peacock and its great globular cluster, NGC 6752. Glowing at magnitude 5.4, it’s the fourth-brightest globular in the sky after Omega Centauri, 47 Tucanae, and M22 in Sagittarius. A 10-centimeter telescope gives a fine view with many individual stars visible. It’s a pity that many observers overlook this cluster because of the two brighter ones, but I guarantee that once you’ve have seen it, you’ll add it to your list of favorites.

Star Dome

The map below portrays the sky as seen near 30° south latitude. Located inside the border are the cardinal directions and their intermediate points. To find stars, hold the map overhead and orient it so one of the labels matches the direction you’re facing. The stars above the map’s horizon now match what’s in the sky.

The all-sky map shows how the sky looks at:

11 p.m. December 1

10 p.m. December 15

9 p.m. December 31

Planets are shown at midmonth